Most computer vision initiatives do not fail because the model is inaccurate. They fail because data quality issues surface too late, after deployment timelines slip, costs increase, and trust in the system begins to erode. In many cases, the root cause is not the algorithm itself, but how the training data was labeled and validated.

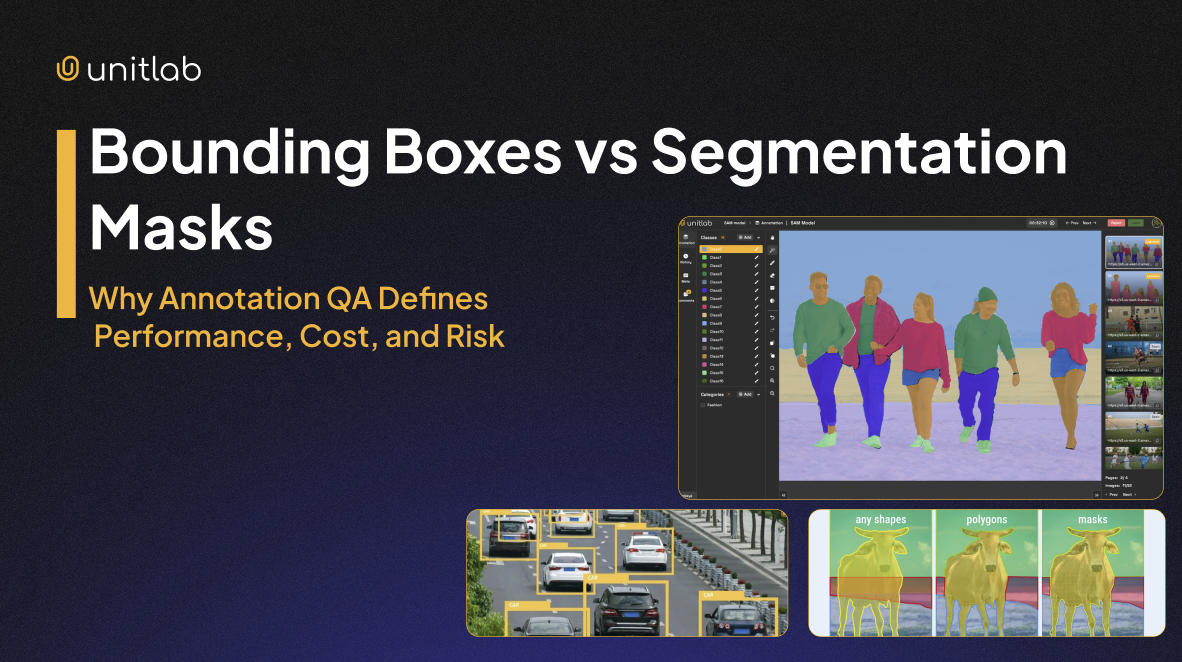

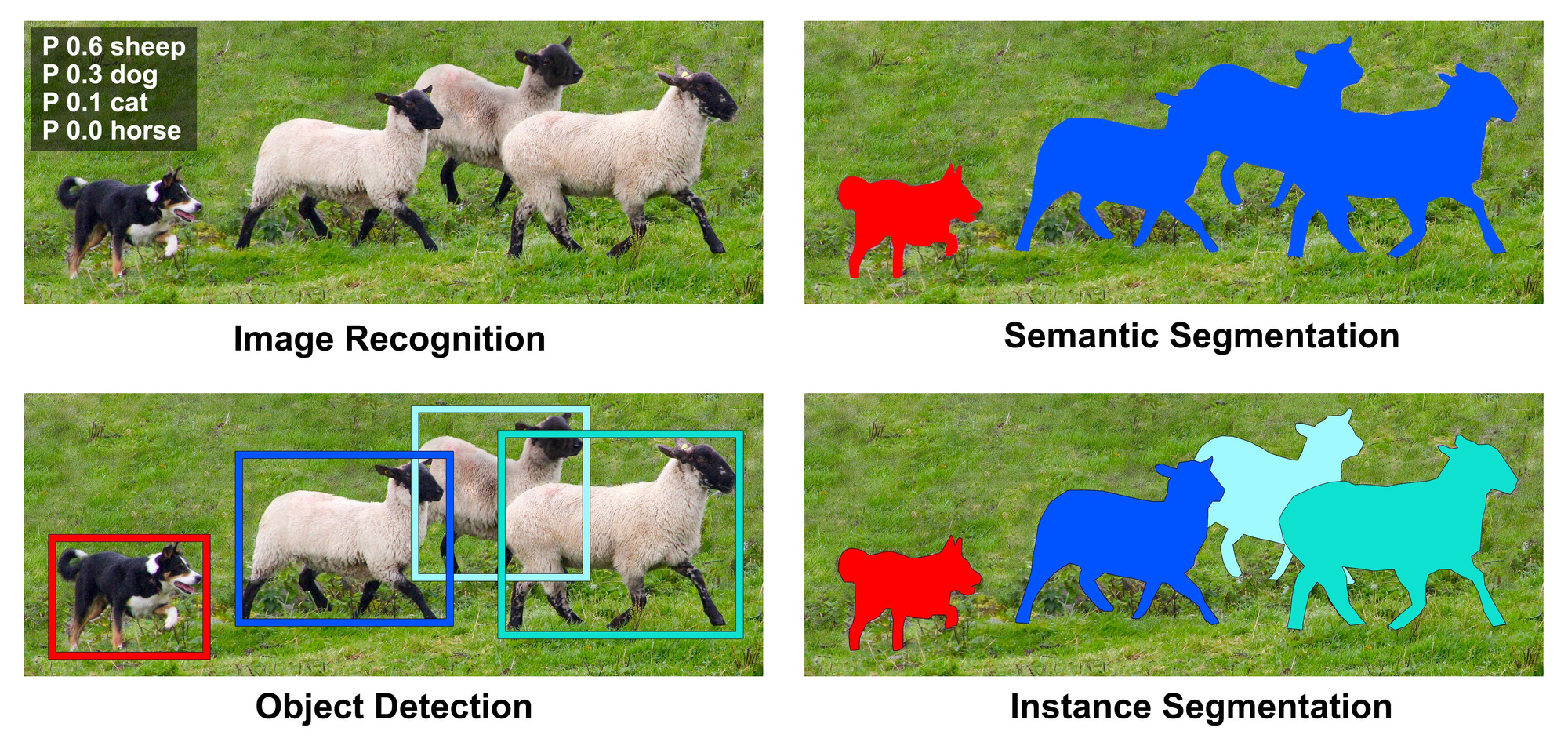

Bounding boxes and segmentation masks form the foundation of most computer vision systems, yet they introduce very different risk profiles. Bounding boxes are fast and scalable, but they often hide spatial inaccuracies during early development. Segmentation masks deliver higher precision, but they also increase annotation complexity, making quality issues harder to detect and more expensive to fix.

This is where annotation QA becomes a business decision rather than just a technical one. As datasets grow and labeling becomes more granular, insufficient QA leads directly to rework, delayed releases, and unpredictable production performance. Teams that underestimate this tradeoff often face higher costs and longer time to value later in the lifecycle.

Understanding the limitations of bounding boxes, the hidden risks of segmentation masks, and where annotation QA matters most is critical for building computer vision systems that scale reliably and deliver measurable business impact.

Bounding Boxes: Fast, Scalable, and Easy to Trust

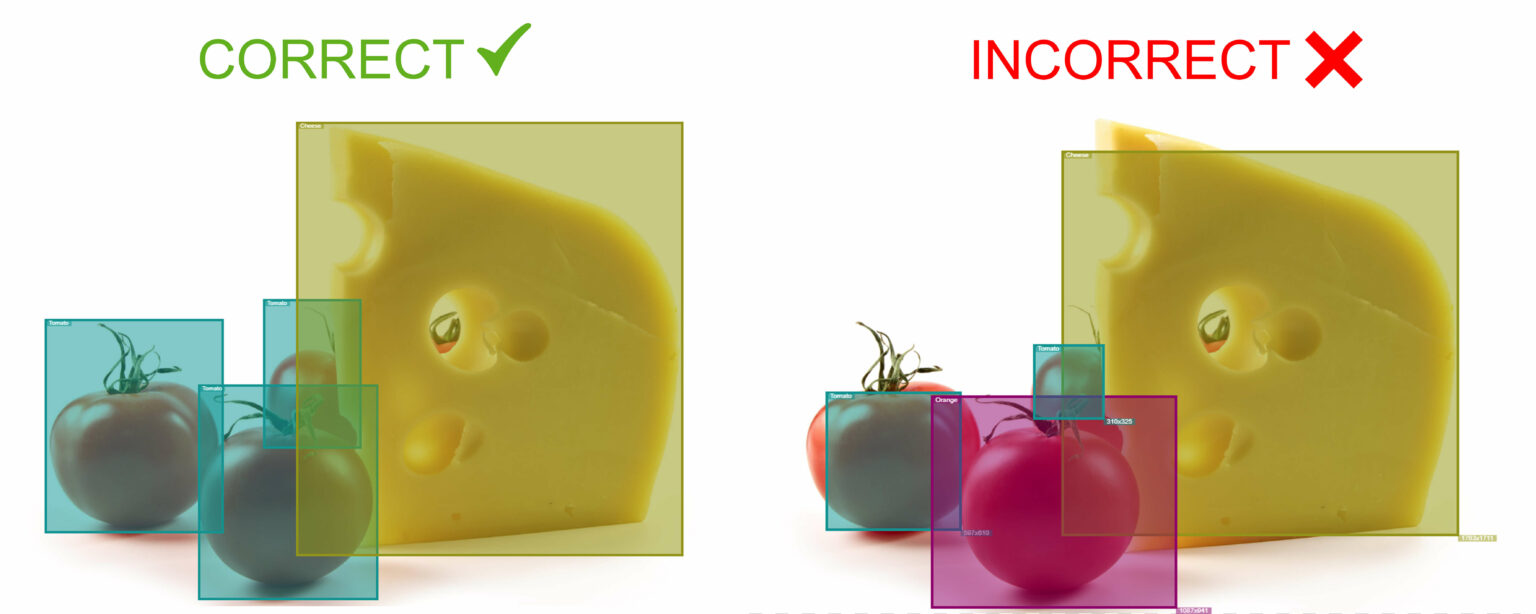

Bounding boxes are the most common annotation type in computer vision because they optimize for speed and scale. When teams need to label millions of images or video frames, bounding boxes provide a practical balance between annotation cost and usable signal. This makes them the default choice for many object detection pipelines, especially in early-stage development or cost-sensitive projects.

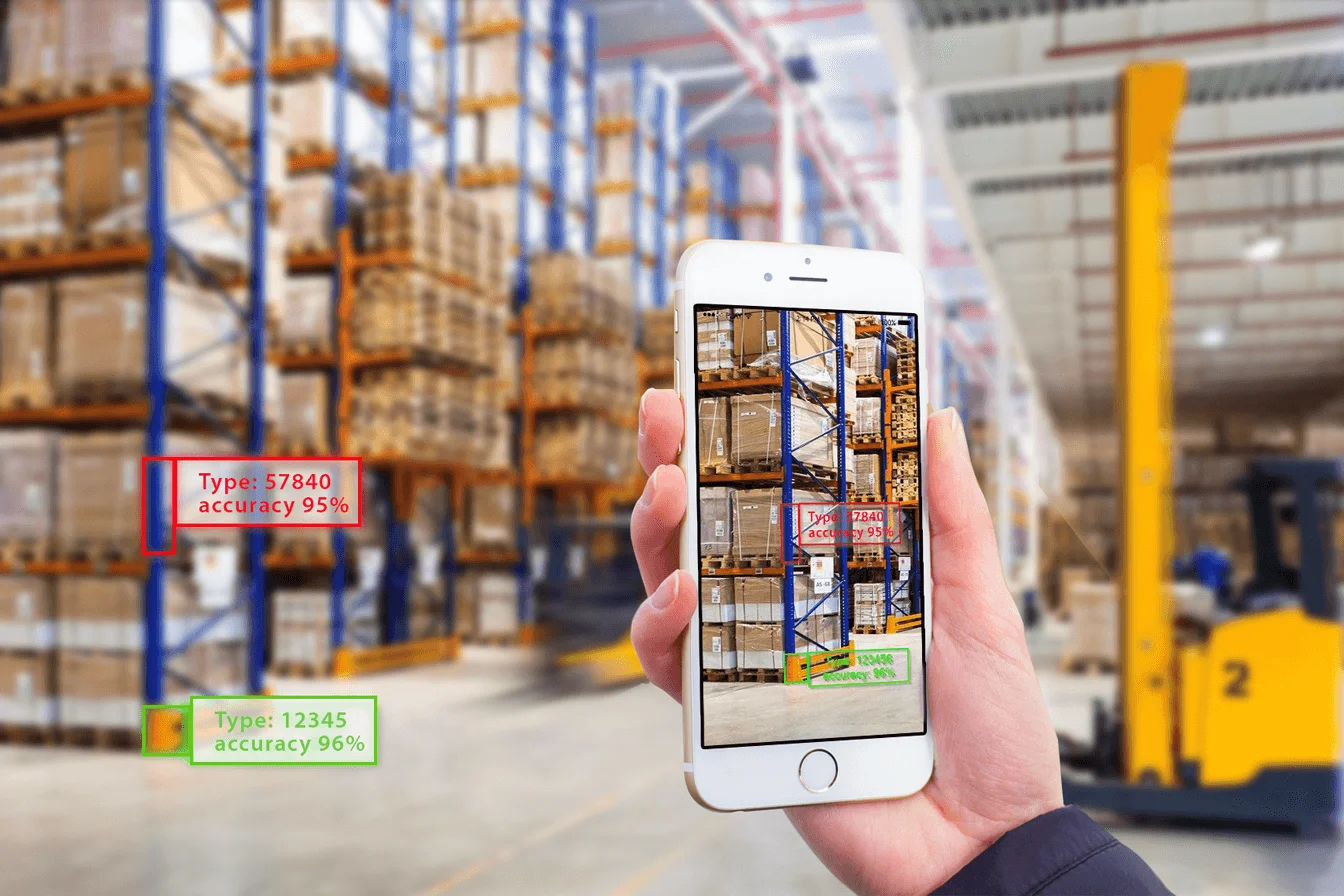

From an operational perspective, bounding boxes feel predictable. Annotation throughput is high, guidelines are simple, and reviewers can quickly scan for obvious issues. Most data annotation tools and computer vision annotation platforms are heavily optimized for bounding box workflows, further reinforcing their adoption across industries such as retail, autonomous systems, logistics, and manufacturing.

However, this simplicity also creates a false sense of confidence. Bounding boxes reduce complex object shapes into rectangular regions, which means many spatial inaccuracies remain visually acceptable during review. Slight misalignment, loose boxes, or partial object coverage rarely appear as critical issues in isolation. Over large datasets, these small inaccuracies accumulate and directly affect how models learn object boundaries and context.

At a high level, these tradeoffs explain why bounding boxes remain popular, while also introducing long-term quality risks in production systems.

| Aspect | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Annotation speed | Very fast to produce at scale | Encourages minimal spatial precision |

| Cost efficiency | Lower labeling and QA cost | Hidden downstream rework cost |

| QA complexity | Easy to review visually | Hard to detect subtle misalignment |

| Scalability | Well-suited for large datasets | Error accumulation over time |

| Production risk | Low upfront risk | Medium long-term risk if QA is weak |

In controlled development settings, these limitations are easy to overlook.

In production environments, this becomes a hidden risk. Models trained on imperfect bounding boxes may show acceptable benchmark metrics while failing under real-world conditions such as occlusion, scale variation, or crowded scenes. Because bounding box errors are subtle and distributed, teams often attribute performance issues to model architecture or data drift rather than annotation quality.

This is why bounding boxes are often described as “easy to trust.” The workflow feels controlled, but without structured annotation QA, important failure modes remain undetected until deployment. To understand why this happens, it helps to look at how bounding box errors typically appear in practice.

Bounding box errors tend to fall into a few recurring patterns. Boxes may be consistently too loose, capturing unnecessary background that introduces noise into the training signal. They may also be too tight, clipping object edges and removing important visual context. In dense or cluttered scenes, bounding boxes often overlap, miss partially visible objects, or fail to capture small instances altogether. Individually, these issues appear minor and easy to overlook. Collectively, they distort how models learn object boundaries and significantly reduce robustness in real-world conditions.

Because bounding boxes are coarse by design, traditional QA approaches tend to focus on object presence and class correctness rather than spatial precision. As long as an object is labeled and classified correctly, subtle alignment issues are often accepted. This creates a gap between annotations that appear acceptable during review and those that are truly production-ready. Without QA designed to detect systematic patterns across datasets, these small inaccuracies accumulate and quietly shape model behavior over time.

This gap becomes far more difficult to manage when teams move beyond bounding boxes to segmentation masks.

Segmentation Masks: Precision That Raises the Stakes

Segmentation masks are introduced when bounding boxes are no longer sufficient to support business or operational requirements. In domains such as medical imaging, robotics, autonomous systems, industrial inspection, and geospatial analysis, models must understand exact object boundaries rather than approximate locations. Segmentation provides this level of precision by labeling objects at the pixel level.

This added precision fundamentally changes the role of annotation in the training pipeline. Unlike bounding boxes, which compress object geometry into rectangles, segmentation masks encode fine-grained spatial detail. Every pixel contributes to how the model learns shape, edges, and context. As a result, annotation quality becomes far more influential, and annotation errors become far more costly.

From a production perspective, segmentation dramatically increases annotation complexity. Labeling takes longer, guidelines are harder to standardize, and visual review becomes less reliable. Boundary decisions that seem minor during annotation can significantly alter model behavior, especially in edge cases where precision matters most.

Moreover, segmentation errors rarely appear as obvious mistakes. They tend to emerge at object boundaries, where annotators interpret edges differently or rush through complex shapes. Common issues include boundary leakage into background regions, small holes within masks, and inconsistent contours across similar objects. In video or sequential data, these inconsistencies often vary frame to frame, further destabilizing the training signal.

Individually, these errors can be difficult to spot, even for experienced reviewers. At scale, they introduce noise that segmentation models are highly sensitive to. Unlike bounding boxes, where small spatial errors may be tolerated, segmentation models learn directly from these imperfections.

| Aspect | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial precision | Pixel-level object understanding | Extremely sensitive to label noise |

| Model capability | Enables advanced tasks and fine control | Higher variance across training runs |

| Annotation effort | Rich training signal | Slow and expensive to produce |

| QA difficulty | Detailed error detection possible | Visual review does not scale well |

| Production risk | High potential accuracy | High cost of missed QA issues |

This contrast helps explain why segmentation initiatives often struggle to scale. The precision that enables advanced capabilities also magnifies the impact of annotation quality decisions. When quality controls are insufficient, higher precision shifts from an advantage to a source of risk.

Because segmentation masks operate at the pixel level, traditional QA approaches struggle to keep pace. Spot-checking a small subset of samples rarely reveals systemic issues. Automated checks can flag extreme cases, but they often miss subtle boundary inconsistencies that still influence model learning.

In production environments, this leads to a familiar pattern. Teams add more data, retrain models, and adjust architectures, yet performance remains unstable. The underlying issue is not insufficient data or model capacity, but inconsistent annotation quality that accumulates across datasets and retraining cycles.

Segmentation does not hide errors. It exposes them, amplifies their impact, and feeds them directly into the learning process. At this level of precision, even small annotation inconsistencies can dominate model behavior and destabilize production systems.

This is the point where annotation QA shifts from a supporting function to a critical control mechanism.

Annotation QA: The Control Layer That Stabilizes Production Systems

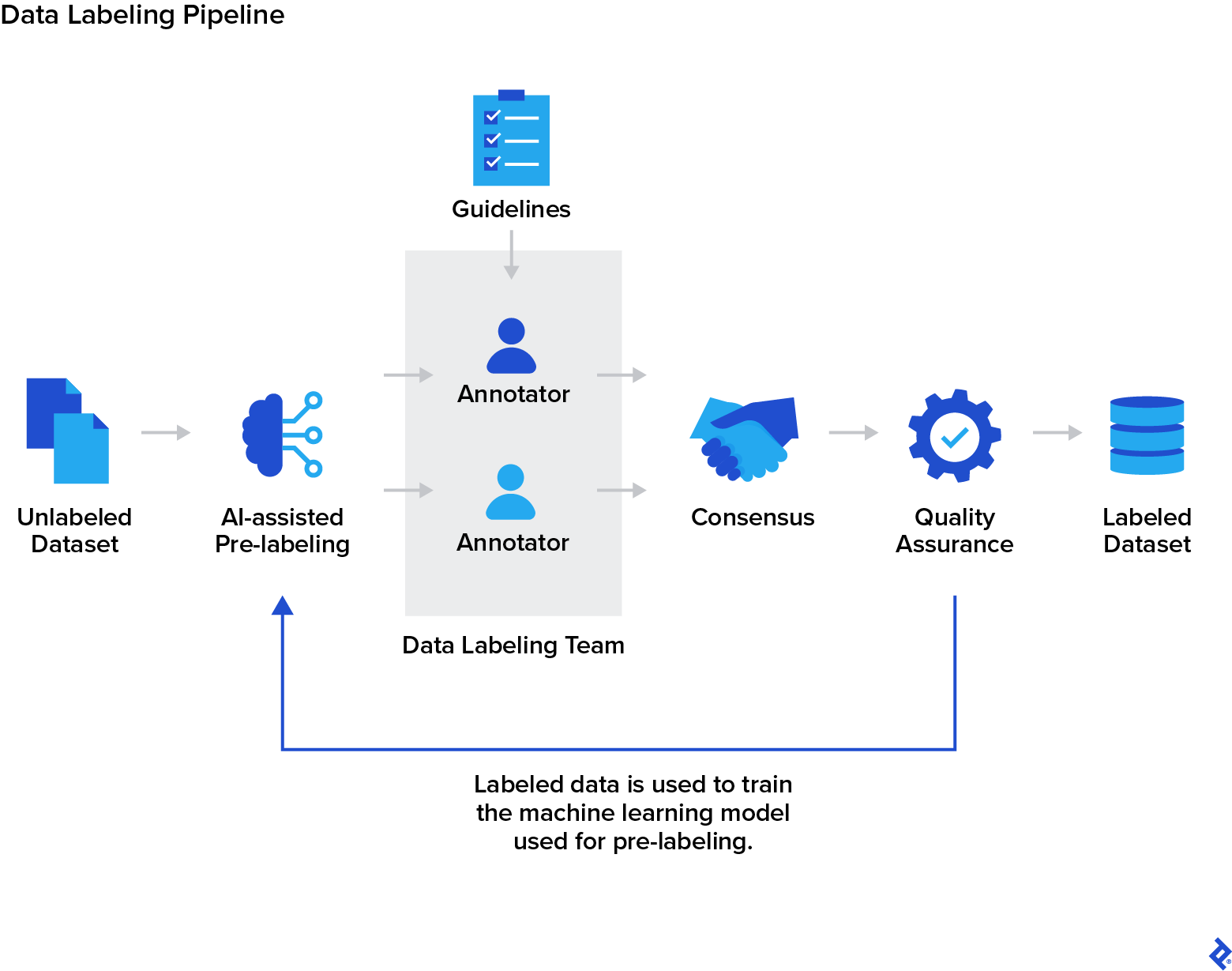

While bounding boxes and segmentation masks fail in different ways, annotation QA is the mechanism that stabilizes both. It sits between raw labeled data and model training, ensuring that quality issues are identified, controlled, and corrected before they propagate into production systems.

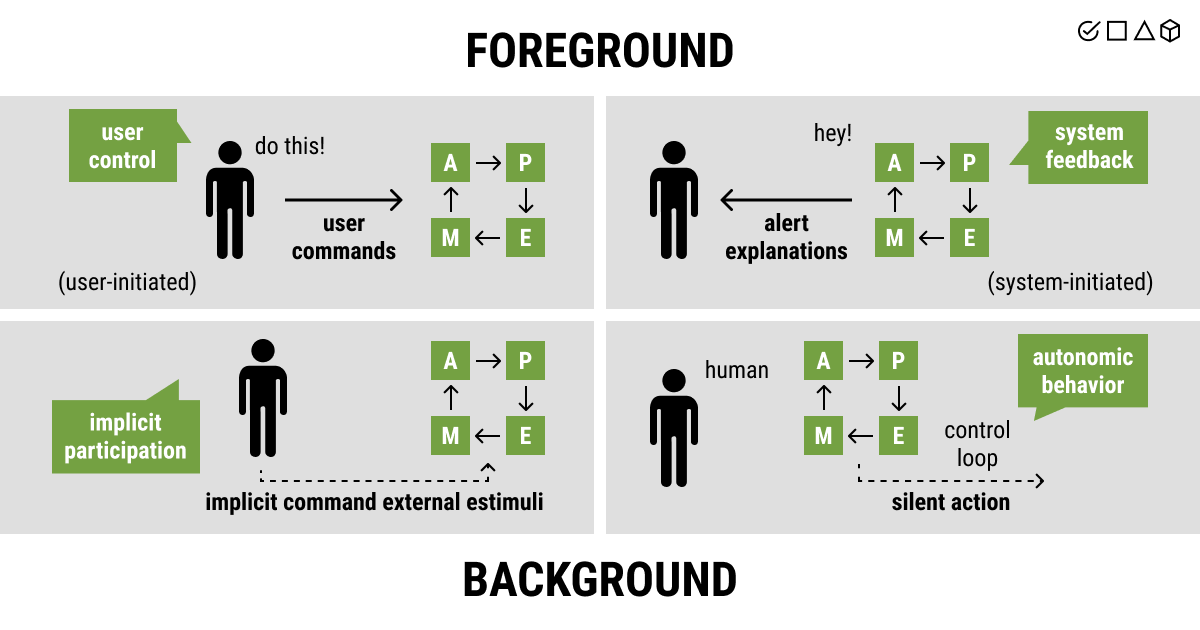

Annotation QA is often misunderstood as a final review step applied after labeling is complete. In production-grade computer vision systems, it plays a much more strategic role. QA acts as a control layer that governs how annotations are validated, how errors are escalated, and how consistency is maintained as datasets grow, change, and are retrained over time.

From a business perspective, annotation QA is not about eliminating every possible mistake. It is about reducing uncertainty, limiting downstream rework, and protecting model reliability as systems scale.

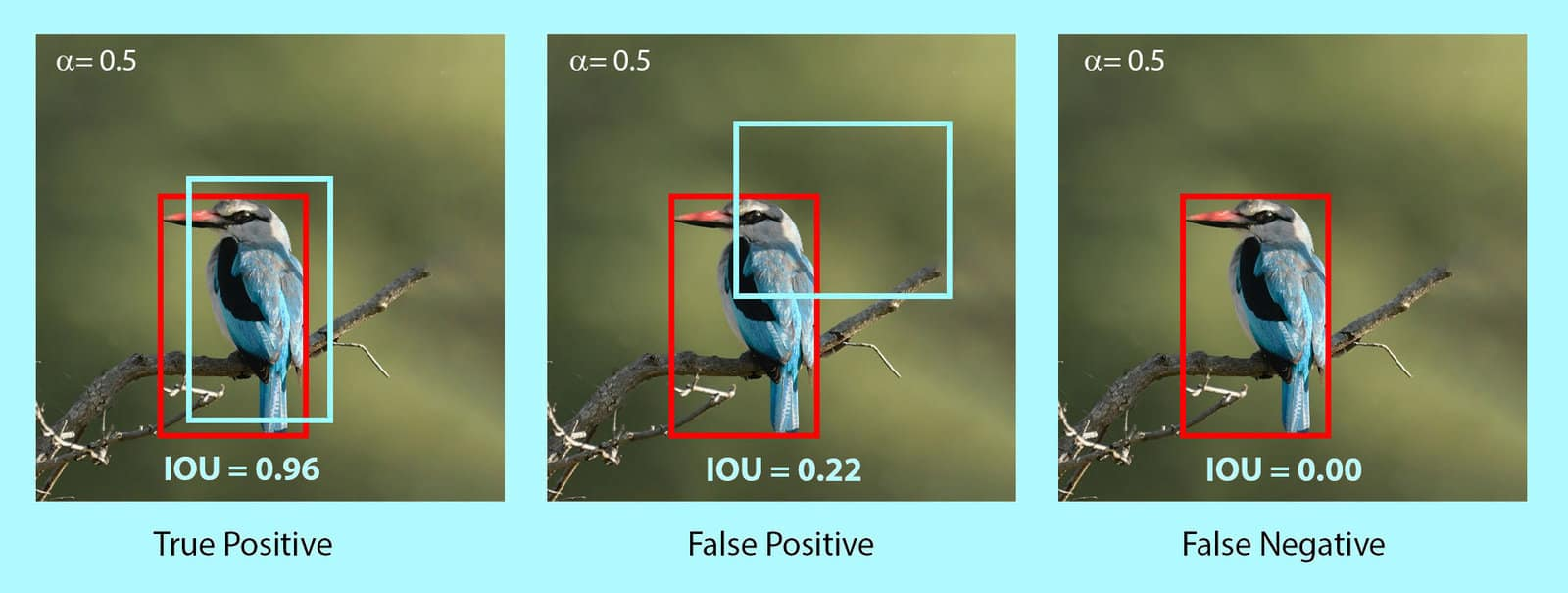

Moreover, bounding boxes and segmentation masks require different QA strategies because they fail differently. Annotation QA adapts to these differences rather than applying a single uniform process. In practice, this difference is most visible in object detection workflows, where QA often revolves around confidence scores, thresholds, and spatial consistency.

For bounding boxes, QA focuses on coverage and consistency. The goal is to detect systematic issues such as consistently loose boxes, class confusion in edge cases, or missed small objects. These problems are rarely catastrophic on their own, but they quietly degrade model performance over time if left unchecked.

For segmentation masks, QA becomes significantly more demanding. Boundary accuracy, shape consistency, and structural correctness directly influence how models learn. Small pixel-level errors can dominate training behavior, making QA essential for stability rather than optimization.

| QA Dimension | Bounding Boxes | Segmentation Masks |

|---|---|---|

| Primary QA goal | Consistency and coverage | Boundary and structural accuracy |

| Error visibility | Relatively high | Low without focused inspection |

| Automation effectiveness | Strong | Partial |

| Human review role | Targeted and light | Critical and selective |

| Impact of missed errors | Gradual degradation | Rapid instability |

This comparison highlights a key insight: QA effort must scale faster than annotation precision. What works for bounding boxes is rarely sufficient for segmentation, especially in production environments.

Furthermore, automation is essential for scale. Automated QA checks can quickly identify missing labels, extreme outliers, and obvious inconsistencies across large datasets. These systems provide speed, consistency, and cost efficiency.

However, automation alone is not enough. Boundary interpretation, ambiguous object separation, and domain-specific labeling decisions often require human judgment. This is especially true for segmentation tasks, where visual nuance directly affects learning outcomes.

Effective annotation QA, therefore, relies on a hybrid approach. Automated systems surface high-risk samples, and human reviewers resolve the cases where precision and context matter most. This balance allows teams to maintain quality without slowing down annotation throughput.

Moreover, when annotation QA is embedded into the data pipeline, it becomes a safeguard rather than a bottleneck. It reduces reannotation cycles, stabilizes model behavior, and shortens time to deployment. More importantly, it protects downstream investments in model training, infrastructure, and deployment.

Teams that delay QA until issues surface often face compounding costs and difficult rollbacks. Teams that design QA as a control layer gain predictability, confidence, and scalability.

Annotation QA does not slow down computer vision systems. It is what allows them to scale safely.

Final Thoughts

Bounding boxes and segmentation masks represent different optimization strategies in computer vision, but neither guarantees production success on its own. Bounding boxes favor speed and scalability, while segmentation masks emphasize precision and control. The difference between success and failure at scale is often determined by how annotation quality is managed.

| Dimension | Without Annotation QA | With Annotation QA |

|---|---|---|

| Data consistency | Inconsistent labels across datasets and annotators | Consistent labeling aligned with clear standards |

| Error detection | Issues surface late, often after deployment | Errors detected early during annotation and review |

| Model behavior | Unstable performance and unpredictable edge cases | Stable, repeatable model performance |

| Retraining cycles | Frequent rework and retraining | Fewer retraining cycles with controlled updates |

| Scaling datasets | Quality degrades as volume increases | Quality scales alongside dataset growth |

| Production risk | High risk of silent failures or instability | Reduced risk through controlled validation |

| Time to deployment | Delays caused by late-stage fixes | Faster releases with fewer surprises |

| Cost efficiency | Hidden downstream costs and reannotation | Lower total cost through early quality control |

What ultimately determines success in production is not model architecture or dataset size, but how annotation quality is managed. Bounding boxes tend to fail quietly, allowing quality debt to accumulate over time. Segmentation masks expose errors immediately, increasing the cost of even small inconsistencies. In both cases, insufficient annotation QA results in unstable performance, repeated rework, and delayed deployment.

This is why production teams increasingly treat annotation QA as a core part of their data infrastructure rather than a final validation step. Platforms like Unitlab are built around this reality, combining structured annotation workflows, quality assurance controls, and human-in-the-loop review to ensure that data quality scales alongside model ambition. By embedding QA directly into the annotation pipeline, teams can identify issues earlier, reduce rework, and maintain confidence as datasets and use cases evolve.

In production computer vision systems, annotation quality is not just a technical concern.

It is a business decision.

References

- Bilal et al. (2024). The Effect of Annotation Quality on Wear Semantic Segmentation by CNN. Sensors, 24(15), 4777. Source

- Chen et al. (2024). Quality Sentinel: Estimating Label Quality and Errors in Medical Segmentation Datasets. arXiv preprint. Source

- Murrugarra-Llerena et al. (2022). Can We Trust Bounding Box Annotations for Object Detection? IEEE/CVF CVPR Workshops. Source

- Uspenyeva (2024). Manual Image Segmentation in Computer Vision: A Comprehensive Overview of Annotation Techniques. Source

- Unitlab (2026). Data Annotation and Annotation QA for Computer Vision. Source