What Is Named Entity Recognition?

Most software systems struggle with raw text. A relational database wants structured fields. A dashboard wants numbers. An automation pipeline wants clear signals. But the information you care about often sits inside unstructured text: emails, invoices, support tickets, contracts, and news.

Named Entity Recognition (NER) is the task of finding and labeling pieces of text that refer to real-world entities, such as people, organizations, locations, dates, and monetary values. It sits inside Natural Language Processing (NLP) and focuses on information extraction from human language.

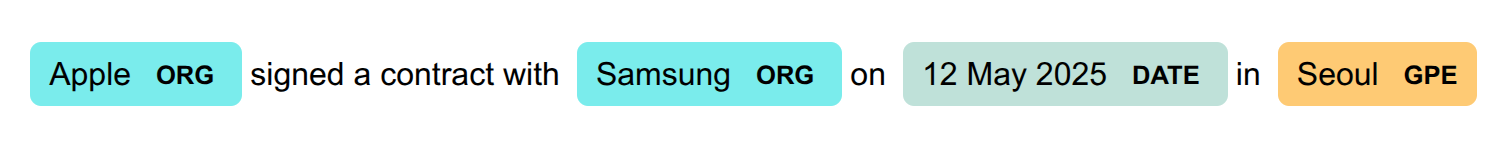

Take this example sentence: “Apple signed a contract with Samsung on 12 May 2025 in Seoul.”

A typical NER model would output:

- Apple → ORG

- Samsung → ORG

- 12 May 2025 → DATE

- Seoul → GPE (Geo-Political Entity)

That shift matters. The sentence stops being just text. It becomes structured data that you can store, search, aggregate, and connect to other systems. This makes NER a core building block in many NLP pipelines; it sits between raw text ingestion and higher-level tasks such as analytics, recommendation, or decision automation.

In this article, we dive deep into NER, its workings, approaches, and challenges.

Let's get started.

How NER Works

A common way to think about NER is sequence labeling. You feed a sequence of tokens. The model predicts a label for each token (or for token spans).

The exact pipeline depends on your NER approach. Deep-learning models, such as transformers, often skip classic feature engineering. Rule-based and classical ML approaches depend on it. Still, the end-to-end flow usually looks like this:

Step #1: Text Input

You start with raw text. For example:

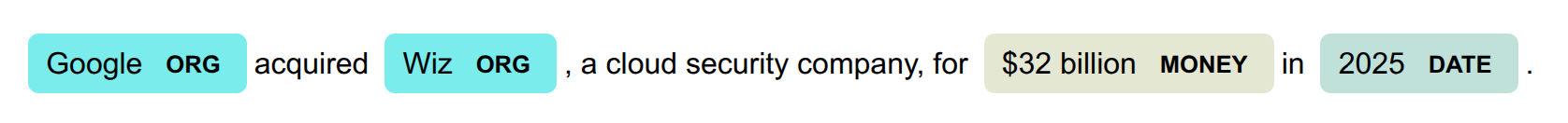

"Google acquired Wiz, a cloud security company, for $32 billion in 2025."

Step #2: Text Preprocessing

You prepare the text so a model can work with it. Tokenization splits the text into tokens:

["Google", "acquired", "Wiz", ",", "a", "cloud", "security", "company", "," "for", "$32", "billion", "in", "2025", "."]

Some pipelines also add part-of-speech (POS) tags to provide grammatical hints. This is common in classical ML setups. It is not required for most transformer fine-tuning workflows though:

[

("Google", "PROPN", "NNP"),

("acquired", "VERB", "VBD"),

("Wiz", "PROPN", "NNP"),

(",", "PUNCT", ","),

("a", "DET", "DT"),

("cloud", "NOUN", "NN"),

("security", "NOUN", "NN"),

("company", "NOUN", "NN"),

(",", "PUNCT", ","),

("for", "ADP", "IN"),

("$", "SYM", "$"),

("32", "NUM", "CD"),

("billion", "NUM", "CD"),

("in", "ADP", "IN"),

("2025", "NUM", "CD"),

(".", "PUNCT", ".")

]

Step #3: Feature Extraction

This step depends heavily on the method you use. In rule-based and classical ML NER, you often build explicit features, for example:

- Contextual Features: Words around the current token

- Orthographic Features: Capital letters, punctuation, digits, word shape

- Lexical Features: Dictionaries and gazetteers (lists of known names)

In transformer NER, the model learns representations automatically from context during pretraining and fine-tuning. You still do preprocessing and alignment, but you usually do not handcraft features.

Step #4: Model Usage

You apply your NER method to predict entity labels:

- Rule-Based Systems: Regex patterns, dictionaries, domain heuristics.

- ML Models: CRF, SVM, and similar supervised learners trained on annotated data

- Deep learning models: BiLSTM-CRF, or transformer-based token classifiers

- Hybrid systems: Rules plus ML or deep learning together

Step #5: Text Classification

The model’s output starts at token level, but you usually want spans.

[

("Google", "ORG"),

("Wiz", "ORG"),

("$32 billion", "MONEY"),

("2025", "DATE")

]

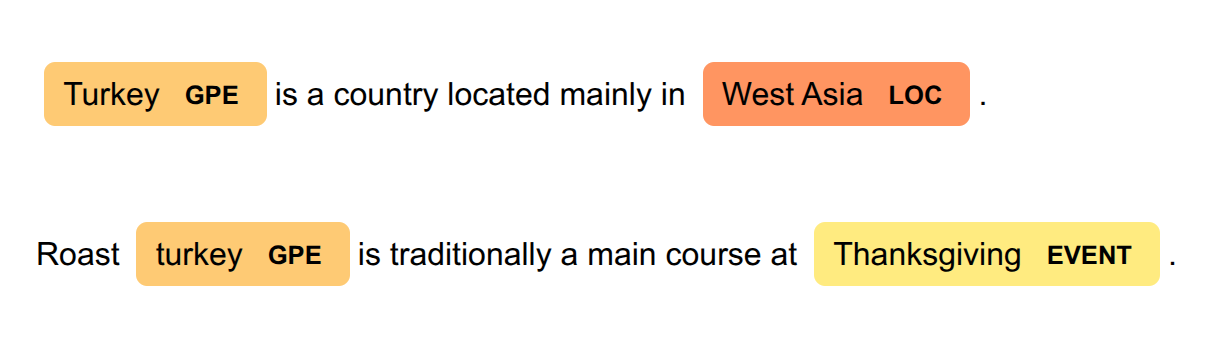

Step #6: Text Post-Processing

Text creates ambiguity, variation, and inconsistency. Jordan can be a person or a country. Turkey can be a country or food. Apple can be a company or fruit. "USA", "US", "U.S.A", "United States", "United States of America", and even "the States" are variations of the same country name in North America.

Post-processing can help by:

- Normalizing surface forms into a single canonical form

- Resolving ambiguity using surrounding context

- Mapping entities to IDs in your database (entity linking)

This step often decides whether NER is actually useful in your product.

Step #7: Output Generation

You usually store results as structured data: JSON, XML, CSV, database rows. The text below shows it in Pandas DataFrame (which can be exported to different data formats):

text type lemma

0 Google ORG Google

1 Wiz ORG Wiz

2 $32 billion MONEY $32 billion

3 2025 DATE 2025

Or you can generate a highlighted text image:

Labels and Tagging in NER

Most introductory examples of NER use standard entity categories Many NER systems start from a familiar set of labels: PERSON, ORGANIZATION, LOCATION. Some widely used label sets expand beyond that. For example, spaCy and other NLP libraries often include labels like GPE, NORP, FAC, EVENT, and WORK_OF_ART.

Here is a common set you will see across many pipelines:

| Labels | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Person (PER) | Names of people or fictional characters. | "Linus Torvalds," "Ada Lovelace," "Obi-Wan Kenobi." |

| Organization (ORG) | Names of companies, institutions, agencies, or other groups of people. | "Alibaba," "United Nations," "MIT." |

| Location (LOC) | Names of geographical places such as cities, countries, mountains, rivers. | "Matterhorn," "Nile River," "Tashkent." |

| Geo-Political Entity (GPE) | Geographical regions that are also political entities. | "Uzbekistan," "Germany," "Tokyo." |

| Date | Expressions of calendar dates or periods. | "October 7, 2023," "the 19th century," "2020-2025." |

| Time | Specific times within a day or durations. | "5 PM," "08:15 AM," "two hours." |

| Money | Monetary values, often accompanied by currency symbols. | "$100," "€50 million," "1,000 yen." |

| Percent | Percentage expressions. | "42%," "3.14%," "half." |

| Facility (FAC) | Buildings or infrastructure. | "Colosseum," "Amsterdam Airport Schiphol," "Stonehenge." |

| Product | Objects, vehicles, software, or any tangible items. | "Android," "Boeing 747," "Linux." |

| Event | Named occurrences such as wars, sports events, disasters. | "World War II," "Olympics," "Hurricane Katrina." |

| Work of Art | Titles of books, songs, paintings, movies. | "Mona Lisa," "I Have a Dream," "Star Trek." |

| Language | Names of languages. | "English," "Arabic," "Turkish." |

| Law | Legal documents, treaties, acts. | "The Affordable Care Act," "Treaty of Versailles." |

| NORP (Nationality, Religious, or Political Group) | Nationalities, religious groups, or political affiliations. | "American," "Muslim," "Democrat." |

General-purpose labels are a starting point, not the end. In real business systems, you often need domain-specific labels:

- Finance: IBAN, transaction reference, merchant, card network, currency

- Healthcare: drug name, dosage, symptom, procedure, lab test

- Legal: clause type, jurisdiction, law reference, party name, case number

This is where taxonomy design becomes a product decision, not just an NLP choice.

Tagging in NER

In practice, NER models do not only predict whether a token is an entity, but also where the entity starts and ends. That’s why tagging schemes exist. Tagging is handled through tagging schemes such as BIO or IOBES.

In BIO, each token is labeled as B for beginning of an entity, I for inside an entity, or O for outside.

| Tags | Description |

|---|---|

| B-XXX | Beginning of an entity of type XXX |

| I-XXX | Inside (continuation) of an entity of type XXX |

| O | Outside any named entity |

With BIO, Our Google example can be tagged in this way:

[

('Google', 'B', 'ORG'), ('acquired', 'O', ''),

('Wiz', 'B', 'ORG'), (',', 'O', ''), ('a', 'O', ''),

('cloud', 'O', ''), ('security', 'O', ''),

('company', 'O', ''), (',', 'O', ''), ('for', 'O', ''),

('$', 'B', 'MONEY'), ('32', 'I', 'MONEY'),

('billion', 'I', 'MONEY'), ('in', 'O', ''),

('2025', 'B', 'DATE'), ('.', 'O', '')

]

IOBES (or BILOU) adds tags that make boundaries even clearer:

- E-XXX or L-XXX marks the end

- S-XXX or U-XXX marks a single-token entity

| Tags | Description |

|---|---|

| B-XXX | Beginning of an entity of type XXX |

| I-XXX | Inside (continuation) of an entity of type XXX |

| E-XXX | End of an entity of type XXX |

| S-XXX | Single-token entity |

| O | Outside any named entity |

Due to this unit-level classification and location-tagging, NER is different from general text classification. In text classification, the model assigns one or more labels to the whole text, such as sentiment or topic.

In NER, the model must decide for every part of the text whether it belongs to an entity and which type that entity is. This makes NER structurally more complex and more sensitive to annotation quality and consistency.

How NER Models Work

NER methods typically fall into four categories.

| Approach | How It Works | Strengths | Weaknesses | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule-Based | Regex and dictionaries with fixed rules | Very precise in fixed formats. Fast. | Fails on language variation | Invoices, templates, IDs |

| ML-Based | CRF or SVM with engineered features | Works with moderate data | Heavy feature work. Weak transfer | Legacy NLP systems |

| Deep Learning | Fine-tuned transformers for token labeling | Strong context. Less feature design | Needs compute. Can overfit | General NER, messy text |

| Hybrid | Rules plus ML or deep models | High accuracy and control | More system complexity | Production extraction pipelines |

Rule-Based Methods

Early NER systems were rule-based, relying on dictionaries, regular expressions, and handcrafted heuristics (gazettes). For example, a rule might specify that a capitalized word after "Dr." or "M.D." always refers to a person with a professional medical degree.

These systems still perform well in constrained settings such as structured invoices or standardized reports, where patterns are stable and predictable. But this method breaks when language becomes flexible, messy, or ambiguous.

ML-Based Methods

Classical machine learning approaches, especially Conditional Random Fields and Support Vector Machines, dominated NER research before deep learning. This approach involves training statistical models on large annotated datasets to automatically recognize different entities.

ML models rely heavily on feature engineering, using word shapes, capitalization, prefixes, suffixes, and part-of-speech tags. While effective, they require significant manual effort and large annotated datasets to adapt to new domains and languages.

Deep Learning-Based Methods

Modern NER systems are almost always based on deep neural networks, particularly transformer models such as BERT, RoBERTa, and DeBERTa. Deep learning shifted NER from feature engineering to representation learning.

Today, transformer models dominate NER because they learn context-sensitive embeddings and fine-tune well on labeled datasets. For NER, a token classification head is added on top of the transformer, and the model is fine-tuned on labeled NER data.

This approach dramatically reduces the amount of task-specific data needed compared to training models from scratch.

Hybrid Methods

Hybrid NER systems combine elements of rule-based, machine learning, and deep learning methods to use the advantages of each.

Rules can catch obvious cases with high precision. Models can handle messy, context-dependent cases. Post-processing can normalize and link entities. For example, a hybrid system might use rule-based techniques to preprocess text and identify obvious entities, followed by a machine learning model to detect more complex cases.

Hybrid pipelines often win in production because they give you control, debuggability, and better edge-case behavior.

Each of these methods has its own set of pros and cons concerning precision, scalability, and resource requirements. The choice of method often depends on the specific application at hand, the availability of labeled data, and the computational resources at hand. So, it depends.

Evaluation Metrics for NER

Token-level accuracy can fool you because most tokens are not entities. So a model that predicts O everywhere can look “good” on accuracy while failing the task completely.

That’s why NER evaluation usually focuses on entity-level metrics: precision, recall, and F1. This belongs to the confusion matrix. Check out our guide if you need a refresher:

Dive into Confusion Matrix and F1 Score

Precision

Precision is a measure that evaluates the proportion of correctly identified positive cases (true positives) among all positive predictions. It is especially important when the cost of false positives is high.

\[\text{Precision} = \frac{TP}{TP + FP} \]

It answers, How many predicted entities were correct? High precision means few false positives.

Recall

Recall is a measure, also known as the true positive rate, that quantifies the proportion of actual positives (positive cases) that are correctly identified by the model. It is crucial for understanding how well the model detects positive cases, especially in high-stakes scenarios.

\[\text{Recall} = \frac{TP}{TP + FN} \]

It answers, How many true entities did the model find? High recall means few false negatives.

F1 Score

The F1-Score is the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, providing a single score that balances the two. High F1-Score suggests a good balance between precision and recall.

\[\text{F1 Score} = 2 \ast \frac{\text{Precision} \ast \text{Recall}}{\text{Recall}+\text{Recall}}\]

Evaluation

Consider the example we've been using:

"Google acquired Wiz, a cloud security company, for $32 billion in 2025."

Here are the actual entities (Ground Truth):

| Entity | Result |

|---|---|

| ORGANIZATION | |

| Wiz | ORGANIZATION |

| $32 billion | MONEY |

| 2025 | DATE |

Imagine our model produced these results:

| Entity | Result |

|---|---|

| ORGANIZATION (True Positive) | |

| Wiz | ORGANIZATION (True Positive) |

| company | Facility (False Positive) |

| $32 billion | NOT DETECTED (False Negative) |

| 2025 | DATE (True Positive) |

We can calculate the metrics now:

TP, FP, FN = 3, 1, 1

Precision = TP/(TP + FP) = 3/(3 + 1) = 0.75

Recall = TP/(TP + FN) = 3/(3 + 1) = 0.75

F1_Score = 2 * (Precision * Recall)/(Precision + Recall) = 0.75

One more detail that matters a lot: dataset splitting. Evaluation is also highly sensitive to how datasets are split.

If sentences from the same document appear in both training and test sets, the model may learn document-specific patterns and produce overly optimistic results. For realistic evaluation, data should be split by document or by source, not randomly by sentence.

Role of Data Annotation in NER Performance

NER is only as good as its labels. Models learn exactly what annotators provide, including their inconsistencies and mistakes. Ambiguity is common, especially when words can belong to different entity types depending on context. Is "Washington" a name, district, or capital?

Ambiguity drives most problems:

- Washington can be a person or a place

- Apple can be an organization or food

- A product name can look like an organization name

Strong text annotation guidelines reduce this by:

- Defining each label with real examples

- Listing clear boundary rules

- Explaining what not to tag

- Handling borderline cases explicitly

Quality control processes such as double labeling, reviewer approval, and targeted audits help maintain dataset reliability. In many real projects, smaller datasets with consistent labels outperform much larger datasets with noisy annotations, especially when models are fine-tuned from strong pretrained checkpoints.

Unitlab AI provides all the necessary infrastructure, tools, collaboration features, QA pipelines for NER projects. Try the platform!

Common Challenges in NER

Production NER fails in predictable ways, which is good news. It means you can create a check list for yourself.

One problem is language coverage. Many languages lack high-quality labeled corpora, so model performance can lag behind English and a few other high-resource languages, such as Russian, Spanish, or German. Cross-lingual and multilingual NER tries to reduce that gap, but it is still an active area of work.

Another problem is domain drift, or simply evolution. Language changes. Product catalogs change. User behavior changes. A model trained six months ago can quietly degrade. This is not a technical problem per se, but of maintenance. You may need to periodically check the corpora for changes, new additions, and removals.

Domain-specific entities (finance, medical, law) add another layer of difficulty. Medical terms, legal references, and finance identifiers can be hard even for humans. For example, in the medical field, identifying complex terms like disease names and drug names is challenging. A general NER model will usually miss them unless you fine-tune on domain data.

Finally, ambiguity and variation never disappear. “Turkey” remains both food and country. Normalization and context-aware post-processing remain part of the job.

Conclusion

Named Entity Recognition turns unstructured text into structured data that systems can store, search, and analyze. It works by labeling sequences of tokens with entity types and boundaries, then grouping those tokens into meaningful spans such as names, organizations, dates, and amounts.

Because language and business requirements evolve, NER systems require continuous updates to datasets, models, and post-processing rules to remain effective over time.

Need a platform that provides all the features necessary for creating a dataset for NER? Try Unitlab AI, an automated and accurate data platform:

Explore More

- Text Annotation with Unitlab AI with a Demo Project [2026]

- Top 5 Text Annotation Tools in 2026

- The Ultimate Guide to Multimodal AI [Technical Explanation & Use Cases]

References

- Alexandre Bonnet (Dec 19, 2024). What Is Named Entity Recognition? Selecting the Best Tool to Transform Your Model Training Data. Encord: Source

- IBM (no date). What is named entity recognition? IBM Think: Source

- Jules Ratier (Sep 08, 2025). What Is Named Entity Recognition (NER)? Key Concepts and Approaches. Koncile: Source

- Pawan Saxena (Dec 17, 2025). Named Entity Recognition. GeeksForGeeks: Source