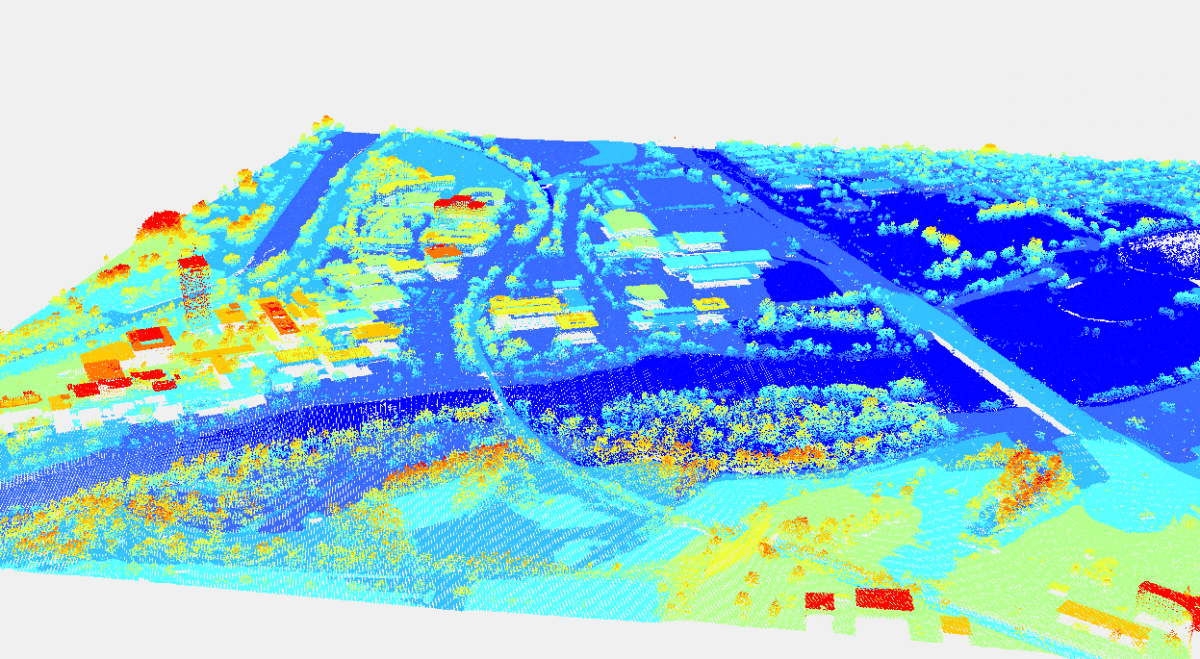

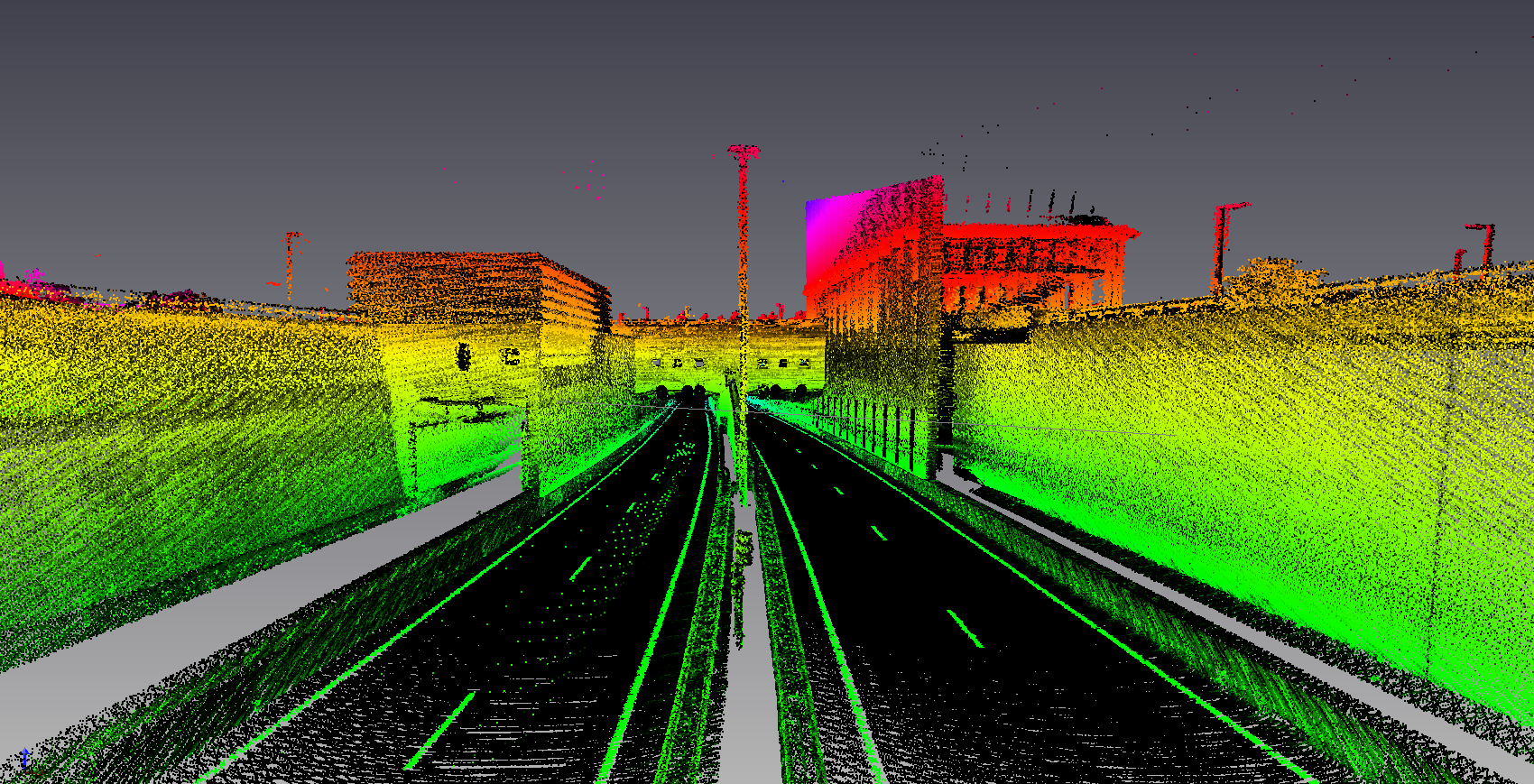

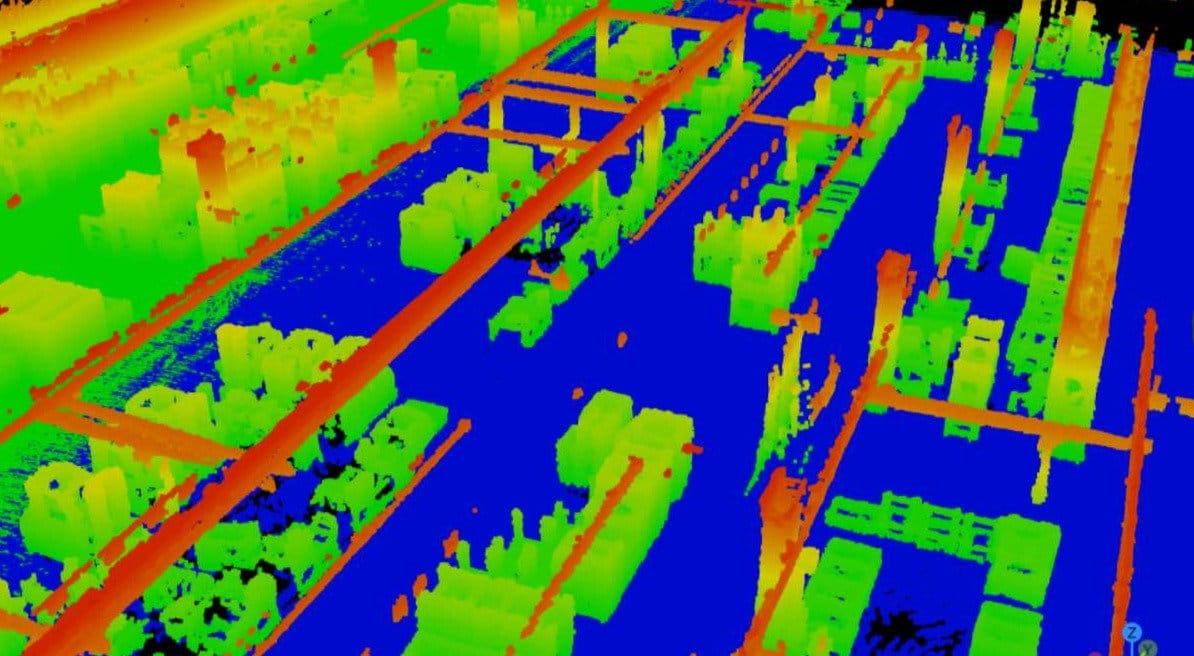

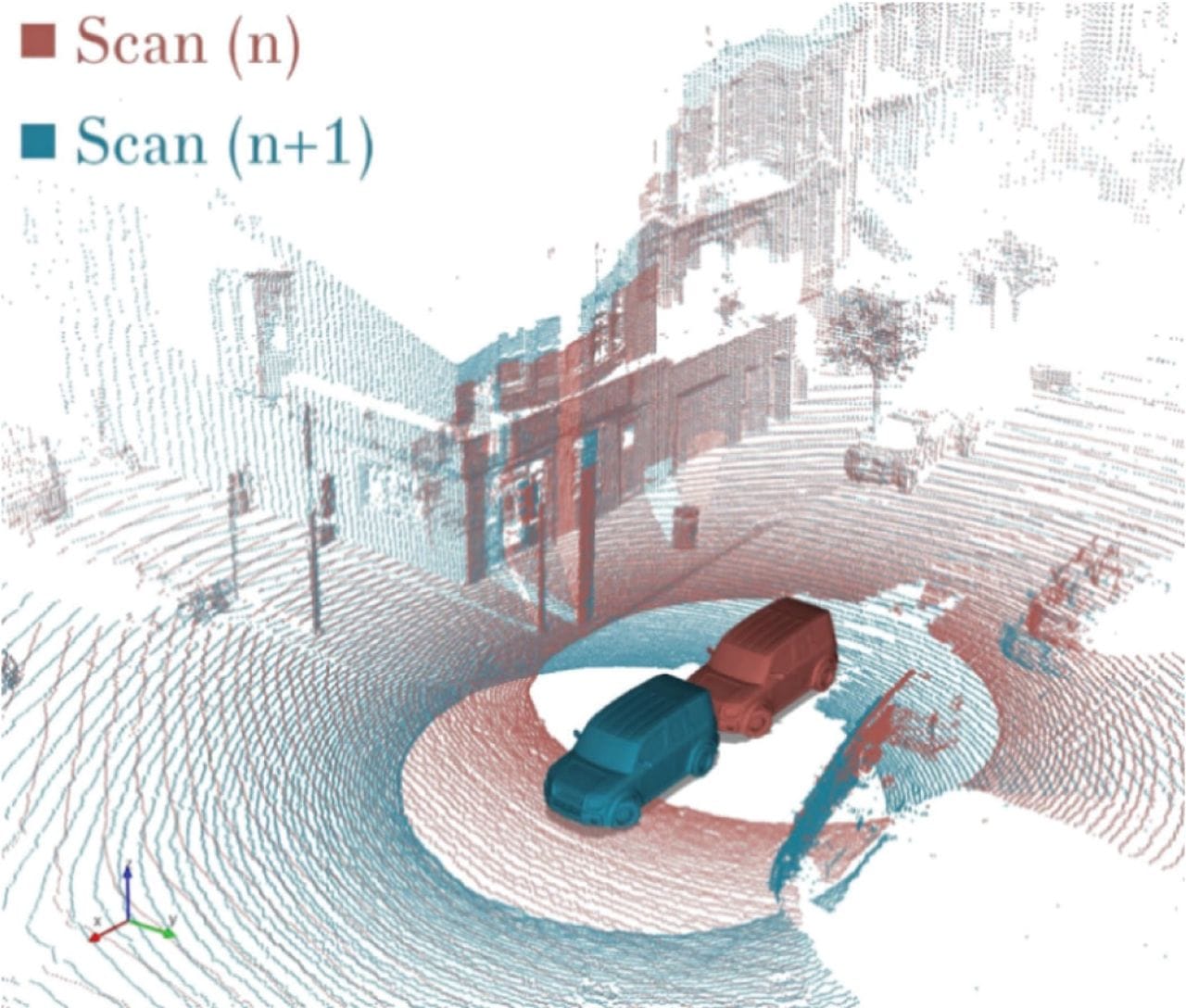

LiDAR is a remote-sensing technology widely used in places where depth and distance are essential. LiDAR uses light beams in order to build a massive raw 3D point cloud which can then be used for 3D modelling, depth estimation, and mapping.

LiDAR Essentials & Applications

However, because LiDAR data is 3D in nature, it is different from 2D/RGB images. It requires different treatment because of geometry, intensity, and other metadata present in its dataset. This is why many different dataset formats evolved over time to suit specific needs. In this post, we will discuss these formats.

We will explore:

- Raw LiDAR dataset formats

- LiDAR annotation types

- Public LiDAR Dataset formats

Let's dive in.

What is LiDAR?

LiDAR means Light Detection and Ranging. It works in the same principle as RADAR (Radio Navigation and Ranging) and SONAR (Sound Navigation and Ranging). While LiDAR emits laser beams to measure depth and distances, RADAR uses magnetic radio waves, and SONAR utilizes sound waves (most common in the underwater environments). These technologies employ different methods to achieve similar goals: to transmit information, measure distances, and extract information.

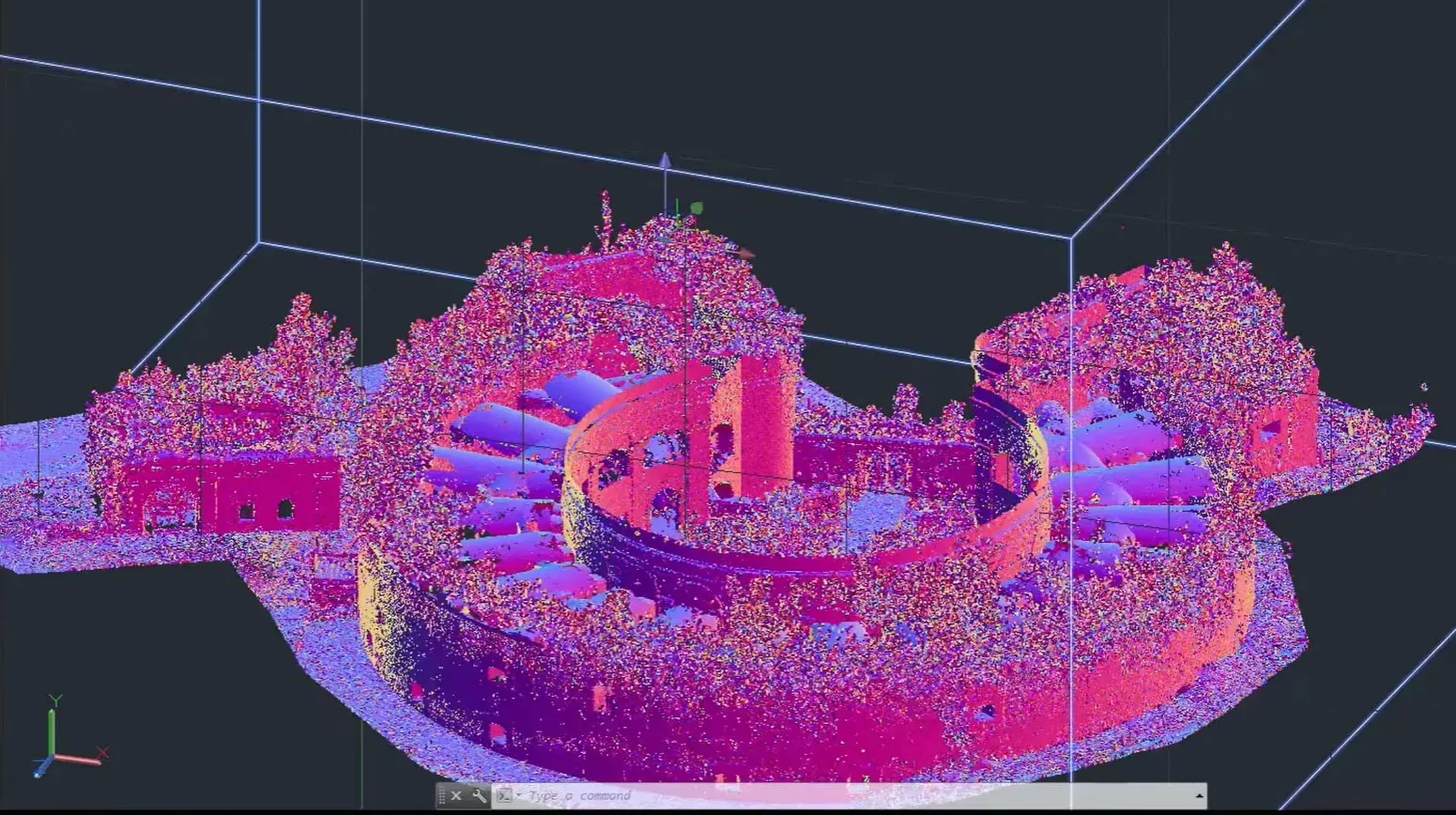

LiDAR measures the distance and depth of a particular area/object by sending laser pulses, receiving their reflectances, and timing how long they take to return, as well as their coordinates. Modern LiDAR systems can send, receive, and process up to 500K light beams per second. These light-reflected points become then part of a massive 3D point cloud.

A typical LiDAR 3D point cloud includes:

- x, y, z coordinates

- intensity (how strong the return is)

- sometimes ring or channel id

- sometimes timestamp per point or per scan

These point clouds undergo several processing steps, cleaned, filtered, annotated, in order to build very precise, detailed 3D models of real objects and topography maps. Because of this precision, LiDAR is commonly used in robotics, aerospace, and self-driving vehicles.

What Makes LiDAR Data Unique

In short, LiDAR data deals with 3D data (x,y,z) while other types of images are 2D-based. These 2D images are sometimes called RGB (red, green, blue) as well.

LiDAR raw data behaves differently than camera/2D/RGB data. It should be stressed that LiDAR deals with 3D data in their true nature, not in the 2D geometry like RGB cameras. Because of this, LiDAR point cloud requires different treatment.

That's the reason why there are key differences when it comes to LiDAR point cloud in practice:

- Sparse geometry: Far objects from the LiDAR scanner can have only a few points, making it difficult to distinguish between say, a tree and a person. That's the reason LiDAR systems are usually accompanied with cameras.

- Real scale: Geometry coordinates are presented in real scales, like meters or foot, not standard pixels in ordinary images.

- Viewpoint dependence: Occlusion and sampling change a lot as the sensor moves.

- Multiple frames matter: Many LiDAR-based tasks need multi-frame sequences (self-driving cars), not single scans. This makes the consistent frames a priority.

- Frames and transforms dominate your pipeline: One small coordinate-frame mismatch breaks training. Inconsistent frames may lead to real-world objects (cars, passsengers) changing their positions or sizes in a random way.

In ordinary 2D image formats like PNG, JPEG, or WEBP, the factors above are not present. But, due to 3D data, they matter for LiDAR raw data formats. For these reasons, raw dataset formats must store geometry and metadata reliably and consistently. Additionally, the dataset structure must keep time alignment intact.

Raw LiDAR Dataset Formats

A LiDAR system, usually composed of a laser scanner, LiDAR sensor, processor, and GPS, emits, receives, and processes laser beams, effectively building a massive raw 3D point cloud. Raw LiDAR formats store point clouds before any annotation.

The formats below store these clouds in their specific way. They define how geometry, intensity, and metadata are written to disk. Your choice of format affects: storage size, read speed, interoperability, and long-term usability.

In practice, however, most LiDAR formats fall into one of two groups: standardized formats for sharing and archiving and task-specific binaries for performance and speed.

The Standard: LAS

LAS is the most widely adopted open standard for LiDAR point clouds. It was designed for airborne and terrestrial LiDAR surveys. You can imagine the LAS format like JSON in the software industry: the standard that everyone knows and understands.

What LAS stores:

- x, y, z coordinates

- intensity

- return number and number of returns

- scan angle

- classification fields

- GPS time

- metadata in the file header

This standard LAS LiDAR file format matters and is used because of a strong standard specification, a stable ecosystem, widespread support by most GIS and LiDAR tools, and a predictable structure across vendors and open-source tools. The LAS has all the features that you would expect from any file standard.

However, LAS comes with its own trade-offs. Its usability and reliability come at a cost of slower processes at scale. Although LAS is binary, it is not compact; it may become a bottleneck in large scales.

Compressed Version: LAZ

Teams solve the compactness problem by compressing LAS into LAZ at storage and transfer. LAZ is essentially a compressed variant of LAS. It preserves the exact LAS structure but reduces file size. In most cases, LAZ is almost the same as LAS, but differs in small details.

Large-scale teams utilize LAZ opposed to LAS because of lossless compression, 5x to 20x smaller files, identical semantics to LAS, and support by most modern LiDAR toolchains. You can imagine LAZ as Apache Parquet in modern data workflows.

An important detail of LAZ is that compression/decompression adds a small processing CPU cost, but disk I/O savings usually outweigh it though. Because of this, LAZ is common for large archives, cloud storage, dataset transmit and distribution.

Essentially, from a data pipeline perspective, you store LiDAR point clouds in LAZ, but you treat LAZ as LAS after decoding for usage/3D modeling.

Robotics: PCD

PCD stands for Point Cloud Data. It originated in robotics and research environments on top of other formats that can process 3D point data.

PCD supports binary or ASCII storage, flexible fields, and arbitrary point attributes. This type of file format appears often due to a relatively simple structure, easy integration with robotics stacks, and fast prototyping, testing, and debugging.

However, this simplicity comes at a cost, as you may imagine. PCD has its own share of shortcomings. You hit problems in production due to inconsistent field naming, missing metadata conventions, and limited standardization across datasets.

Therefore, PCD works best when you control the full pipeline end-to-end, portability and standardization are not a priority, and LiDAR raw datasets are small to medium scale.

Fast Binary: BIN

BIN is not a standard LiDAR file format. It is a common file format used in many industries. Binary means just 0 and 1, machine code. It usually means raw binary dumps of float values.

In the case of LiDAR, a typical structure looks like: x, y, z, intensity as 32-bit floats, tightly packed arrays, and one file per frame. This binary structure for LiDAR raw, massive point clouds bring many benefits in the form of extremely fast loading, minimal parsing overhead, and easy streaming into data pipelines.

However, due to its simplicity and binary nature, BIN does not include some essential metadata that makes LiDAR unique in the first place. These include measurement units (meters/foot), coordinate frames, and semantic meaning. These metadata are usually included in separate calibration files, dataset documentation, and code/industry assumptions. The fast, minimal overhead might be less beneficial due to this dual work.

However, BIN formats dominate a few specific areas where speed and performance are essential, as in autonomous vehicles or in large-scale LiDAR training pipelines. In short, BIN file formats trade portability and standardization for speed and performance.

Plain Text: ASCII

ASCII formats store point clouds as text in a similar way to CSV (comma-separted files). In fact, CSV, TSV, or .txt files are all extensions of ASCII file formats. The first/top line is the header, which specifies column names, like x, y, z, intensity, time. Each line below represents one point.

Engineering teams may store LiDAR points in ASCII-based file formats because this approach provides human readability, easier debugging and testing, and a quick inspection.

However, apart from small datasets, real teams in production usually abandon ASCII-based standards because of massive file sizes, slow parsing, floating-point precision issues. While BIN formats trade portability for speed, ASCII-based formats trade speed and size for readability.

That said, storing 3D point clouds is useful for toy datasets, debugging exports, teaching and demos. It does not scale, but is super useful in other areas.

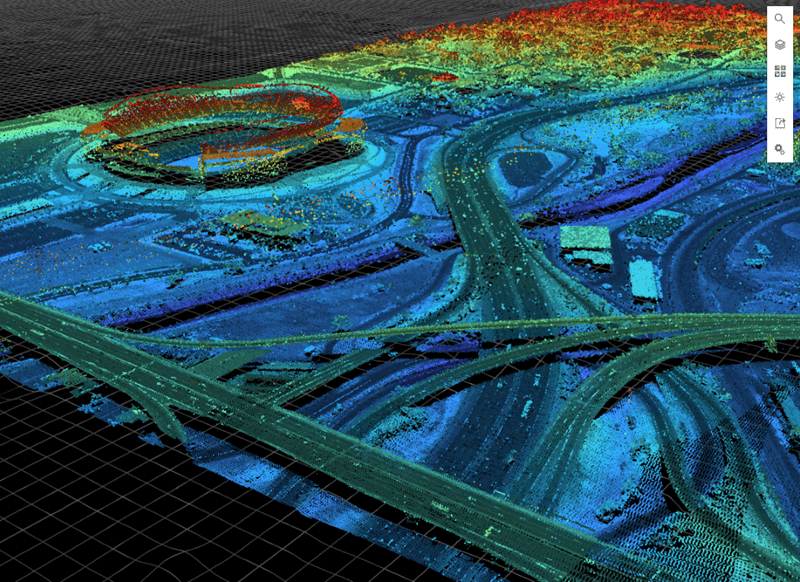

Rasterized Data: GeoTIFF

GeoTIFF is not a point cloud format. It stores rasterized representations derived from LiDAR. In simple terms, rasterization is the process of turning mathematical shapes (vectors) into a grid of colored dots (pixels). The most notable exam is video-game graphic rendering; GPUs render coordinates, lines, and curves into realistic 2D pixels in modern games.

Typical LiDAR-based examples include digital elevation models (DEM), digital surface models (DSM), and height maps. However, this rasterization process for raw LiDAR point clouds mean that you lose individual point geometry, multiple returns, abd vertical structure.

But you trade them for fixed grid representation, compatibility with raster GIS workflows, easier visualization and analysis at scale. All LiDAR dataset formats come with inherent trade-offs, you might have noticed.

GeoTIFF works when you care about terrain, not objects, vertical resolution matters more than point density, and downstream tasks expect rasters. Therefore, this dataset format is common in mapping, environmental analysis, and remote sensing.

Industry-Specific Formats

Some domains depending on their specific use cases and trade-offs may define their own formats. Some examples include proprietary airborne survey formats, vendor-specific scanner outputs, and internal research formats. You may come across them in practice in the real world.

These specific formats exist for various reasons. Most common ones are hardware constraints, legacy systems, and/or domain-specific metadata needs. Although rare, these formats can and do exist. However, they have their own documentation for engineers to use them properly.

These proprietary formats come with their own risks. Because of a small set of users and lack of community support, these formats support limited tooling and integration, usually have less-than-excellent documentation, and difficult long-term relevance and maintenance. If you inherit such formats in practice, your best might be to convert them early into LAS, document assumptions, validate geometry and units.

Raw formats shape everything downstream because they are considered the source of truth. Once the first pipe in the pipeline is affected, it affects every other pipe. Once geometry is misread or metadata is lost, annotation quality suffers. That cost shows up later as model failure, not file errors.

This separation between raw and annotated datasets is crucial; one raw 3D point cloud can be used for many different annotation formats.

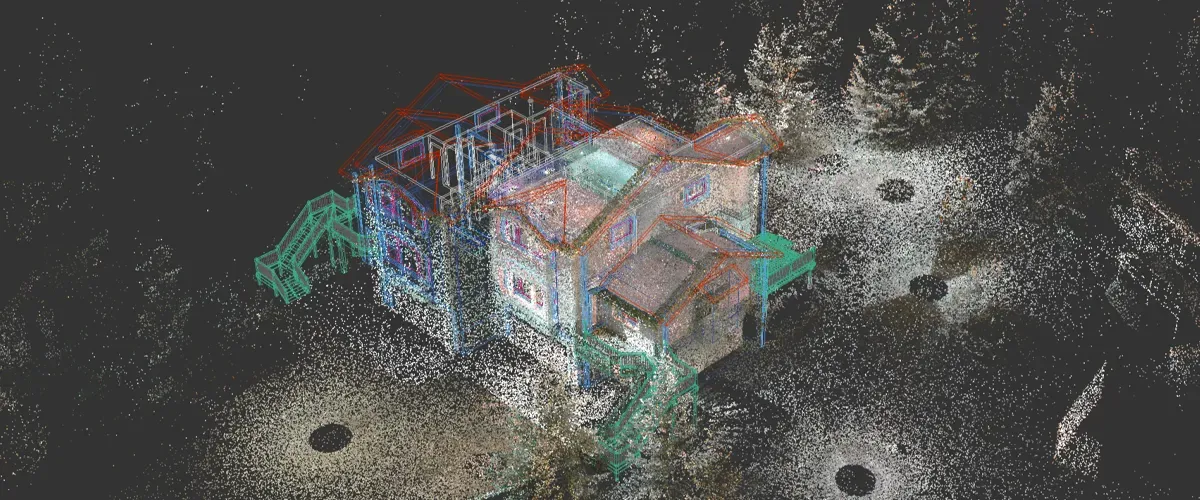

Annotated LiDAR Dataset Formats

Annotation formats sit on top of raw point clouds. Annotations are usually the same concepts as they are in 2D/RGB images. What changes is the dimensions; instead of bounding boxes, we might draw 3D cuboids. Instead of segmenting pixels, we segment cloud data points.

A LiDAR annotation format determines the task the label is for. It specifies which coordinate frame a particular label is inm and how labels should be mapped to frames and timestamps.

Do check out our post on image annotation types in 2D if you need a refresher for them:

Image Annotation Types in 2D/RGB images

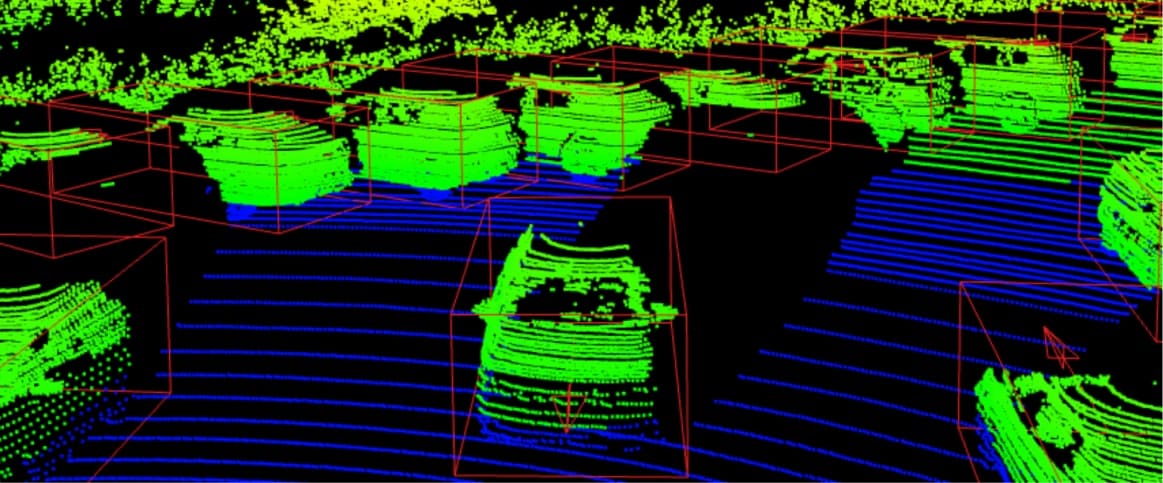

3D Cuboids

3D cuboids are essentially 2D bounding boxes in 3D. They are most common for object detection in 3D. Main use cases include self-driving cars and robotics detection.

Typical fields:

- class name

- box size (l, w, h)

- box position (x, y, z)

- rotation (often yaw)

- optional velocity, attributes, confidence

Because 3D geometry is added in cuboids, there are notable differences from bounding boxes. First of all, rotation axis can differ across coordinate systems. You must state absolute units and frame as well for cuboids. One similarity is that some LiDAR datasets define the box center at the bottom, others at the geometric center.

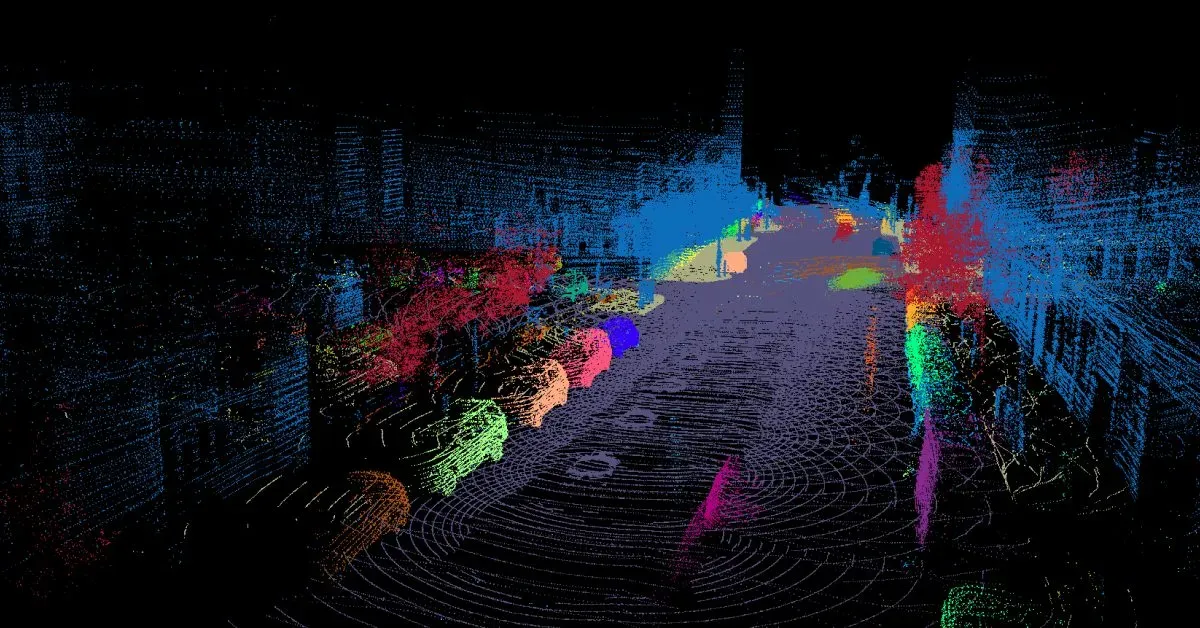

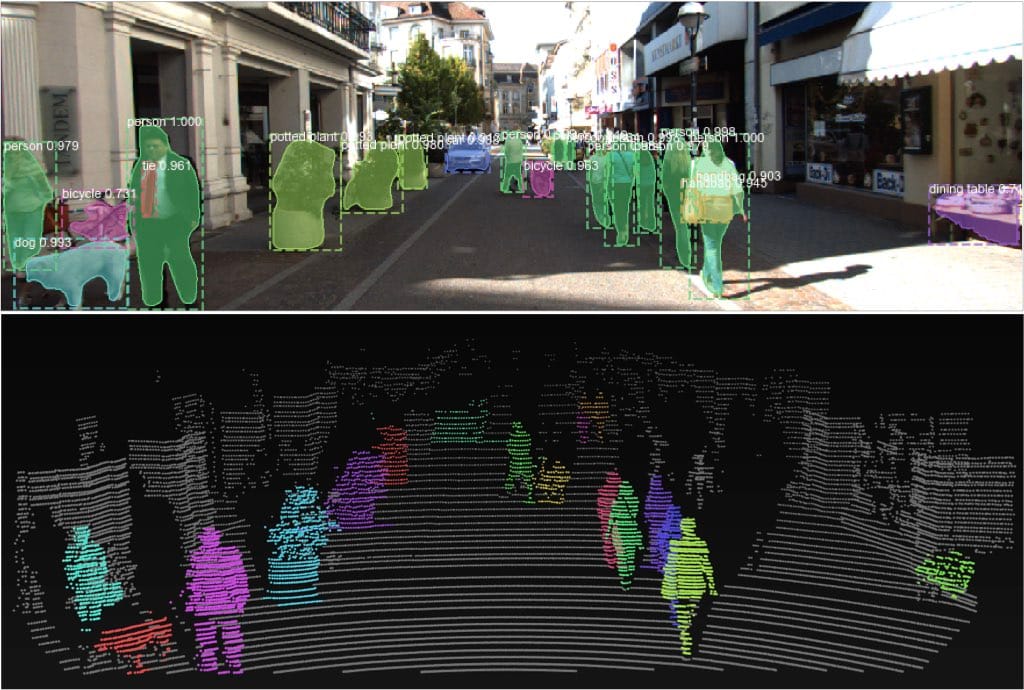

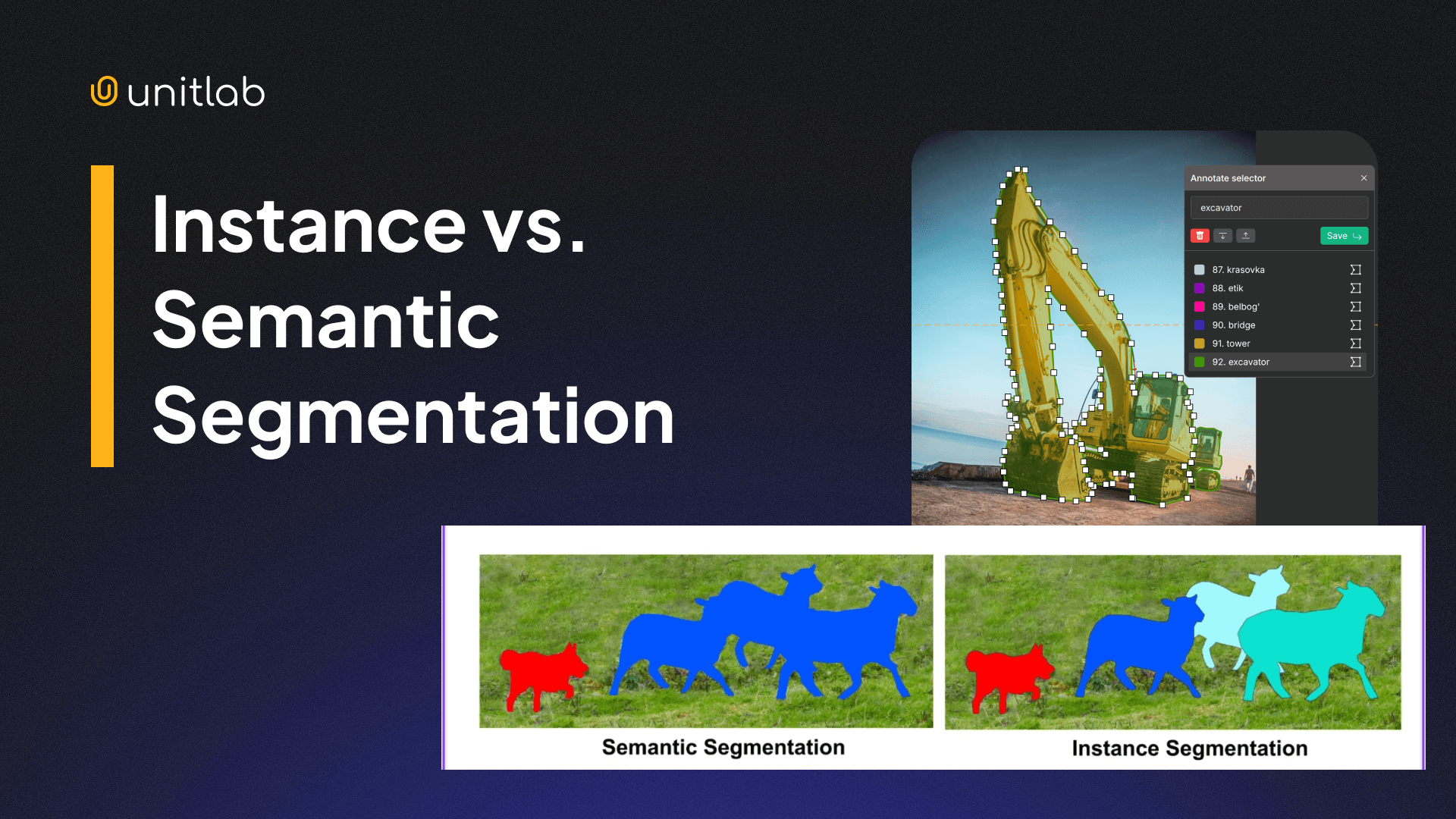

Semantic segmentation

Essentially, LiDAR semantic segmentation is the same as 2D semantic segmentation. 3D labels 3D point clouds, RGB images label pixels. The nature of the task is the same: you assign a class to each point, creating semantics.

The storage patterns are usually one label per point (array aligned to point order), and labels stored per frame (with strict indexing rules).

Instance segmentation

Instance segmentation differs from semantic segmentation in that the first detects and separate multiple instances of the same object (pedestrian in the image above), while the second doesn't. You group cloud points into object instances of a certain entity.

Common representations include per-point instance id, per-point class id, optional tracking id for sequences. These ids are necessary for multi-frame LiDAR datasets.

Check out our post for the difference between instance and semantic segmentation in 2D images:

Instance vs Semantic Segmentation in RGB images

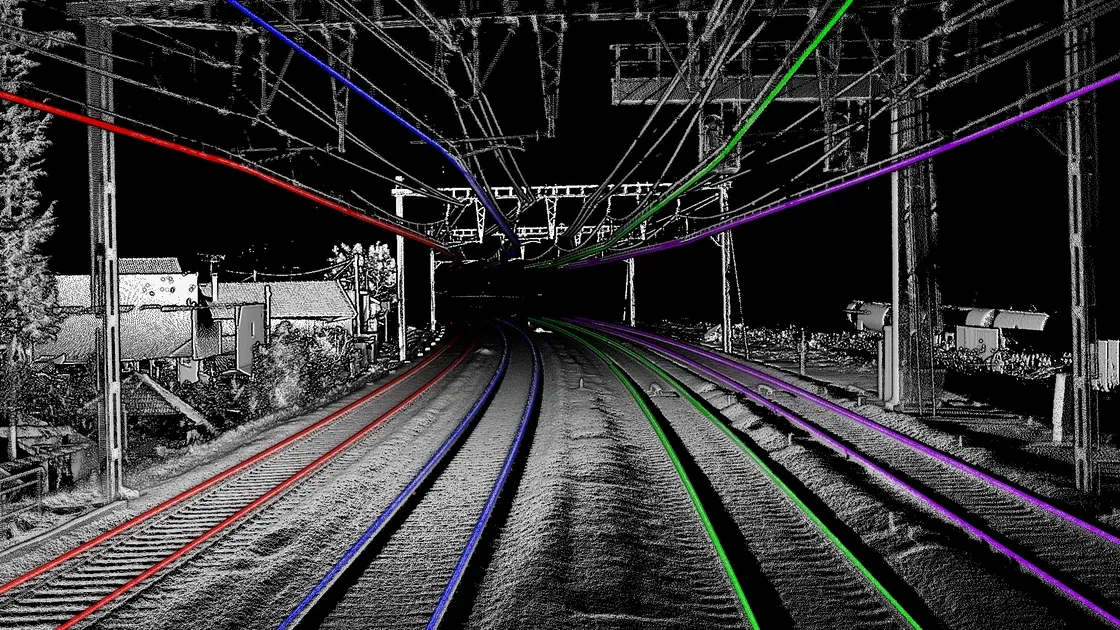

Polylines and lanes

Polylines and lanes are usually used for HD (High-Definition) mapping of areas and road structure tasks.

Typical annotation formats include polyline vertices in a chosen frame, topology (lane connections), attributes (lane type, boundaries). This forces you to treat “dataset formatting” as “graph formatting”.

Choosing the Right LiDAR Dataset Format

Which format to choose for your raw point cloud? Well, the answer is, it depends.

Each format above has its own trade-offs and use cases. You determine what you need, what your task is, and choose the most suitable format. If none of the mainstream datasets fit your super niche use case, then it might make sense to use industry-specific dataset format.

That said, here are some rules of thumb for you to consider. if you need portability across tools, use LAS/LAZ for interchange in mapping and GIS workflows, and clear unnecessary metadata files when you must stay lightweight. This way, you gain easier sharing, storage, and integration, along with fewer custom parsers.

If you need speed at scale, use packed binaries for point clouds, container formats for streaming sequences, separate metadata and index files. This provides you with faster training input pipelines and smaller overhead in distributed training.

If you need clear review and QA workflows, use human-readable JSON/ASCII for labels, strict schemas and versioning, and explicit coordinate frame fields. This way, you benefit from fewer silent bugs and easier debugging when model metrics collapse.

In short, use the LiDAR dataset that fits the most. The dataset format itself does not break your LiDAR annotated dataset; it is the consistency, high-quality annotations, and proper processing.

Common Pitfalls in LiDAR Dataset Formatting

These issues cost weeks because they look like “model problems”. They are format problems. These issues decrease model performance, precision, and accuracy.

Frame mismatch

You label in one frame and train in another. The symptoms are that boxes appear shifted or rotated, and the model never learns stable localization. This inconsistency impedes the model's accuracy and reliability, leading to what is known as AI hallucinations.

The way to address this issue is to store frame id in every annotation and to store transforms with timestamps. Finally, you test by visualizing labels over raw points early. This ensures that objects do not randomly change over frames.

Unit drift

Unit drift refers to unexpected changes in unit metrics across LiDAR dataset frames. This can be meters vs centimeters vs foot, or radians vs degrees. You may think this is a simple fix that engineers can quickly do, but this can happen even at the scale of NASA missions.

The symptoms include objects/boxes explode/decrease in size unrealistically. Yaw/rotation points look random. You fix these errors by fixing units in schema and validating ranges during training and export.

Taxonomy drift

Class ids change across splits or versions. Training might improve but evaluation collapses due to class id changes. The model behaves erraticaly, making the confusion matrix look upside down as a result. You fix this drift by shipping a single source-of-truth taxonomy file and versioning it like code.

Conclusion

LiDAR is a remote-sensing technology that uses lasers to measure distances and estimate depth. This technology tends to give precise, detailed depth information which is used in many industries such as autonomous vehicles, robotics, and 3D modeling.

LiDAR is different from 2D/RGB images in that it is composed of billions of raw 3D points, making it a point cloud. The size, 3D nature, and complexity make LiDAR datasets and annotations a challenge of its own nature.

Due to different needs, several LiDAR dataset formats have evolved, such as LAS, PCD, ASCII-based formats. These formats are raw LiDAR data on top of which annotations are done. This is ingenious; the same dataset can be used for different data labeling purposes.

The right LiDAR dataset format depends on the task at hand (obviously). You may prioritize portability and standardization, or speed and performance, or readability. However, most of the time, LAS/LAZ are suitable for most tasks.

This dataset formatting matters. Strong formatting gives you reliable training, faster iteration, easier tooling interoperability. Inconsistent, unsuitable dataset formats result in silent label bugs that are hard to debug, wasted training runs, and misleading benchmarks, all of which ultimately make your ML models less accurate and useful in the real world.

Explore More

Check out these articles for more on LiDAR technology, datasets, annotation, and applications:

- What is LiDAR: Essentials & Applications

- LiDAR Annotation and Dataset

- What is Computer Vision Anyway? [Updated 2026]

References

- Fredrik Moger (no date). What File Format Is LiDAR Data? Atlas Blog: Source

- Hojiakbar Barotov (Dec 24, 2025). LiDAR Annotation and Dataset. Unitlab Blog: Source

- IBM Think (no date). What is LiDAR? IBM Think: Source

- Tom Staelens (May 02, 2024). Mastering Point Clouds: A Complete Guide to Lidar Data Annotation. Segment AI: Source