AI and machine learning models, and computers in general, aren’t biased by nature. At their core, they’re just tools designed to solve specific problems.

But that doesn’t mean they’re neutral in practice. In fact, these tools can end up being quite biased, not because someone deliberately made them that way, but because the data they learn from often carries hidden assumptions and imbalances.

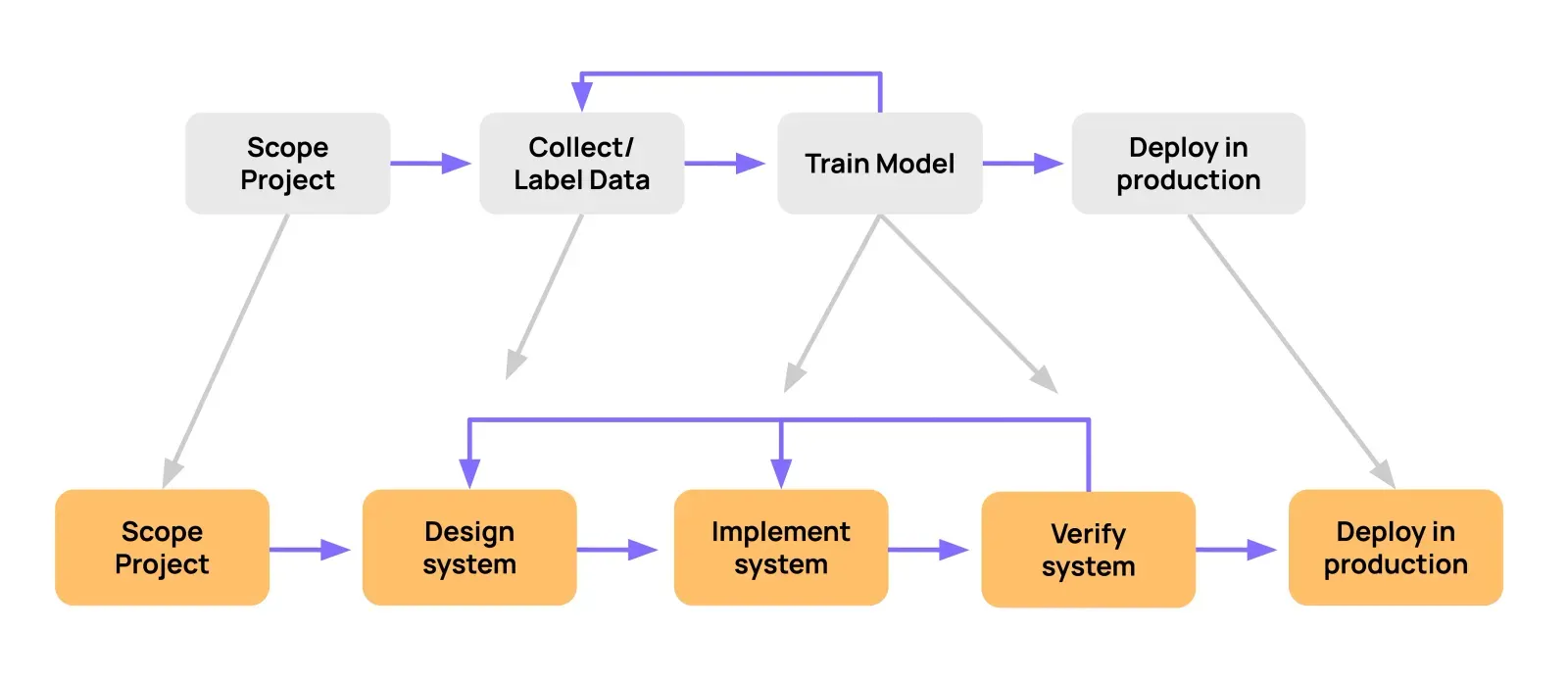

To build practical and effective AI/ML models free from bias, we usually need a huge amount of data. There’s a common rule of thumb called the 10x rule, which suggests the dataset should be roughly ten times larger than the number of parameters in the model. But before this data can be used, it has to go through several steps: collection, cleaning, augmentation, and labeling. Synthetic data can also be used to augment training datasets, helping to reduce bias and address data scarcity.

Biases can sneak in at any stage of this pipeline, but they’re most common during the data collection phase. Data selection decisions at each stage can introduce bias, affecting the fairness of the final model.

In this post, we’ll look at three key sources of bias that often make their way into the final model, which you can identify and address in your own AI projects:

- Bias in the data itself

- Bias in the algorithms

- Bias introduced by human annotators

But first, let’s be clear on what we mean by “bias” in this context.

What is Bias?

Machine learning bias refers to systematic and unfair disparities in the output of machine learning algorithms. These biases can manifest in various ways and are often a reflection of the data used to train these algorithms.

— Wikipedia

Put simply, bias is a pattern of error in a model’s outputs that systematically favors or disadvantages certain groups, classes, or scenarios. This results in real-world consequences where select groups are unfairly disadvantaged. These biases can lead to discriminatory outcomes and biased results in AI systems, impacting fairness and trust.

A model might underperform on minority groups, misrepresent ideologies, or entirely overlook rare edge cases; unless you’re explicitly looking for these issues, they may go unnoticed until they cause real harm in production. Biased outputs can have significant negative impacts in real-world applications, further emphasizing the need to identify and address these issues.

Intuitive Example of Bias: Financial Markets

To understand bias more intuitively, consider a real-world example from the world of finance: herd mentality. This is the tendency of investors to copy what others are doing, not based on logic or analysis, but simply because “everyone else is doing it.” You buy a certain popular stock, say Nvidia, because you read it is rising; everyone else around you is buying it as well.

This is a classic phenomenon where market participants (traders, investors, and analysts) tend to ignore their own analysis and rational decision-making in favor of copying others and doing what others are doing. Herd mentality is a form of cognitive bias, where emotional shortcuts and social influence override objective reasoning.

In case you didn’t know, this herd-like investor behavior was one of the primary factors that fueled many asset bubbles from the dot-com bubble in 2000 to the GameStop short squeeze in 2021.

If you bought shares of an overhyped company such as GameStop simply because it was trending online at Reddit, you’ve experienced herd bias firsthand. It’s an emotional shortcut that overrides independent, slow, rational thinking. It’s a powerful force that leads to irrational decisions and inflated markets.

Confirmation bias and pre-existing beliefs can further reinforce herd behavior, as individuals unconsciously seek out information that supports the crowd’s actions and their own assumptions.

Bias in machine learning is similar: it’s often not about malicious intent, but about inherited assumptions, i.e. patterns passed down from flawed data. And the consequences are real, whether it’s an algorithm making incorrect predictions, mistreating particular groups, or reinforcing outdated norms.

Where Bias Enters

As mentioned above, the bias can enter in any part of our machine learning pipeline. However, three points are especially susceptible to bias: ML bias in data, algorithms, and humans. Transparent and inclusive decision making processes are crucial in AI development to ensure that these sources of bias are identified and addressed effectively.

Human oversight plays a vital role in identifying and mitigating bias throughout the machine learning pipeline, helping to ensure ethical and equitable outcomes before, during, and after model deployment.

Bias in Data

This bias occurs when the dataset used to train an AI model doesn’t accurately reflect the diversity and complexity of the real world. These gaps can take many forms: an overrepresentation of certain classes, missing data from specific regions or groups, or an overreliance on polished or ideal scenarios.

Selection bias and exclusion bias can occur when certain groups are underrepresented or systematically omitted from the dataset, leading to unrepresentative samples and skewed model outcomes.

Here are a few common types of data bias that have been well documented:

- Language bias: Most large language models are trained primarily on English content. As a result, they tend to prioritize Western perspectives while downplaying or ignoring ideas expressed in other languages. For example, search queries on concepts like “liberalism” often return Anglo-American definitions that may not align with interpretations in other parts of the world.

- Recall bias: This occurs when certain data points are more likely to be remembered or recorded than others, affecting the accuracy and representativeness of the training data.

- Gender bias: AI models often reflect the same gender imbalances found in historical data. A notable example comes from Amazon’s 2015 hiring tool, which began penalizing résumés from women simply because past data showed that most successful applicants were men. The model learned from this skewed history and started downgrading applications that mentioned women’s colleges or female-coded language.

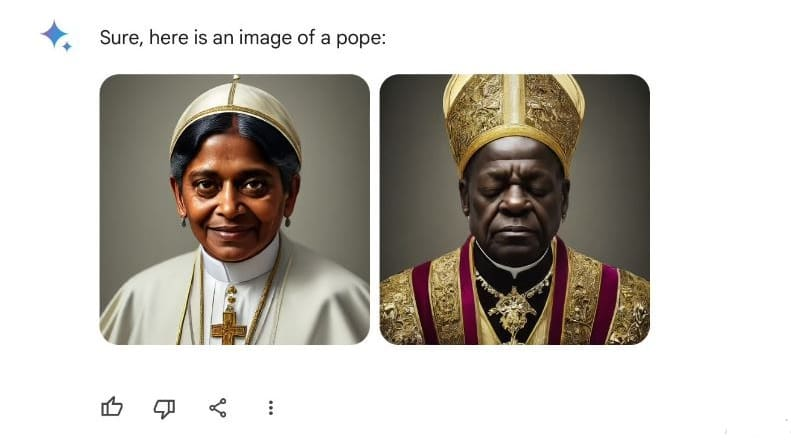

- Political bias: losely tied to language bias, political bias arises when models lean toward a particular ideology based on the data they were trained on (liberal, moderate, conservative, etc). In efforts to appear politically neutral and achieve political correctness, some systems may even strip away meaningful context: sacrificing current and historic facts in the name of balance (like generating an image of a woman pope, which cannot be true).

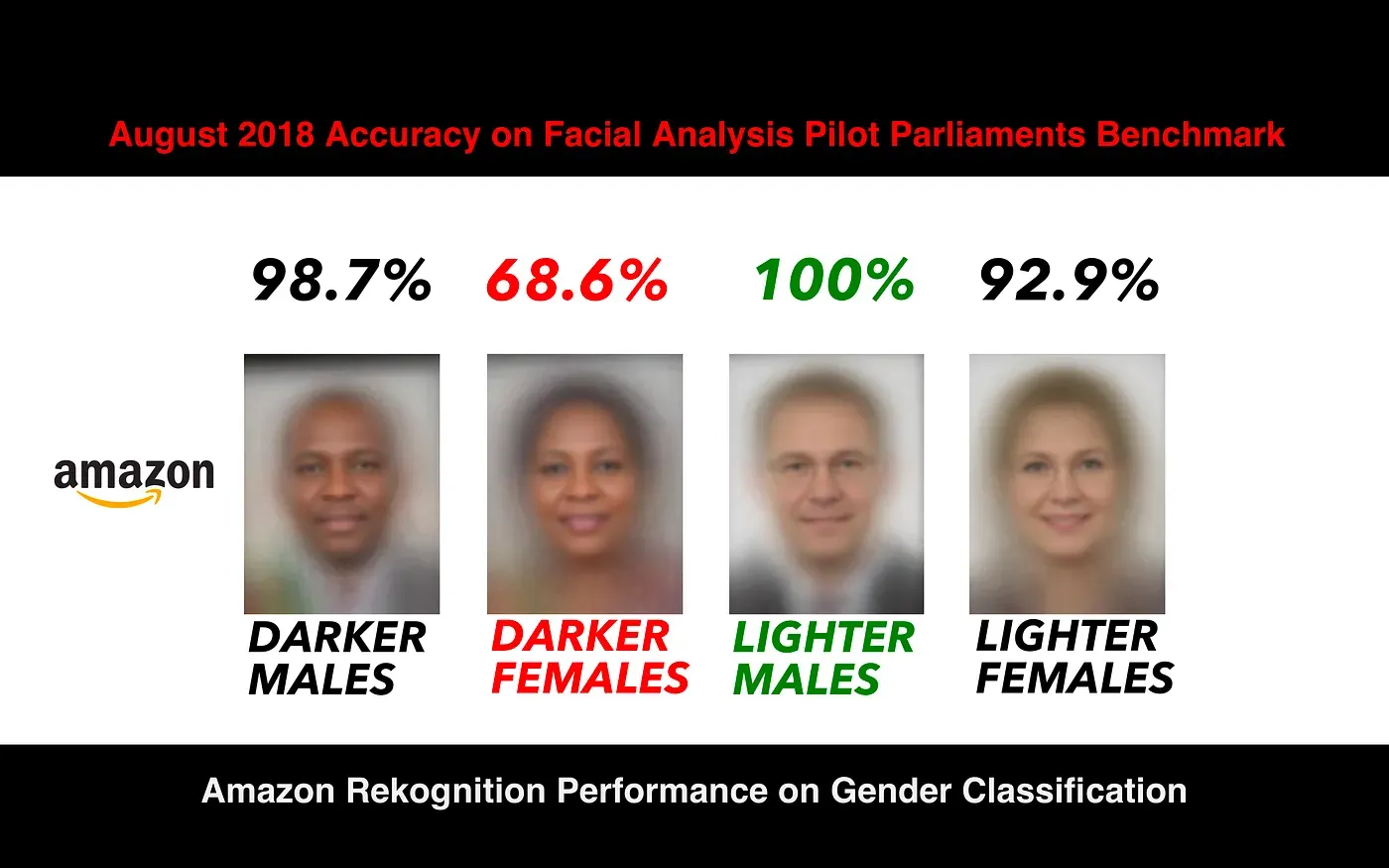

- Racial bias: Many datasets used in healthcare, law enforcement, and facial recognition have historically underrepresented people of color. The resulting models that don’t work as well for these groups, leading to higher error rates, misidentifications, or unequal access to services.

A widely cited example is facial recognition technology. Multiple independent studies have found that these systems perform significantly worse on female individuals with darker skin tones.

The root cause? The datasets used to train them contained disproportionately more images of lighter-skinned individuals. This imbalance means that, even if the algorithm is not inherently biased, its training history makes it less accurate for certain groups. Biased data and issues in the original training data can lead to poor model performance and unfair outcomes for underrepresented groups.

To address this type of bias, we have written an extensive guideline before:

Common Dataset Mistakes | Unitlab Annotate

Human Bias during Labeling

Even if your data is diverse and balanced, you are not in the clear yet. The next layer of ml bias can emerge during the labeling process, when humans annotate the data used to train your model.

Data annotators are humans, and like all of us, they bring their own perspectives, assumptions, and mental shortcuts into the task. This is what makes them superior to programmed machines; human annotators can take a step back, assess the big picture, and make an informed decision that makes sense.

However, implicit bias and out group homogeneity bias can influence how annotators label data, leading to the reinforcement of stereotypes or misclassification, especially for minority or out-group examples.

Because humans are subjective, this likely affects data labeling. This becomes especially noticeable in subjective labeling tasks, such as classifying emotions in text, drawing segmentation masks, or rating content for toxicity.

In textual intent annotation for example, a sentence as simple as “We should talk later.“ can be interpreted differently. In the English-speaking countries, this often implies disagreement, while this might be a simple factual logistics statement in the Russian culture.

When you add gestures, body languages, and other norms to your training data, there will be a wide gap for potential bias to come in. That’s why clear annotation guidelines are so important.

Additionally, a recent paper, Blind Spots and Biases (Srinath & Gautam, 2024), dives into this issue. The researchers found that annotators often deviated from the intended labels due to cognitive fatigue, reliance on shortcuts, or personal beliefs.

Human biases, including implicit and out group homogeneity bias, play a significant role in shaping labeling outcomes. Even with clear instructions, different annotators interpreted the same data differently, which leads to inconsistencies that ripple into the model’s behavior.

Algorithmic Bias

Algorithms introduce their own form of bias even when the data and annotations are carefully controlled. Models don’t simply reflect datasets; they also reflect the assumptions baked into their architecture, optimization process, and feature selection.

The role of AI algorithms is crucial here, as biases can arise during the process of building models if these algorithms are not carefully designed to account for fairness and mitigate discriminatory patterns.

You see this in several ways:

- Training objectives push models toward patterns that maximize accuracy, not fairness.

- Loss functions treat all errors equally, even when certain errors harm specific groups more.

- Regularization, pruning, and compression can unintentionally suppress minority patterns and over-amplify dominant ones.

- Architectures such as transformers or CNNs favor statistical shortcuts once they discover them. They often latch onto the easiest signals, not the most meaningful ones.

- Models inherit inductive bias from how they’re designed. What they prioritize, ignore, or assume is shaped by architecture choices developers make.

You see this in several ways:

- Training objectives push models toward patterns that maximize accuracy, not fairness.

- Loss functions treat all errors equally, even when certain errors harm specific groups more.

- Regularization, pruning, and compression can unintentionally suppress minority patterns and over-amplify dominant ones.

- Architectures such as transformers or CNNs favor statistical shortcuts once they discover them. They often latch onto the easiest signals, not the most meaningful ones.

- Models inherit inductive bias from how they’re designed. What they prioritize, ignore, or assume is shaped by architecture choices developers make.

Language models are also susceptible to learning and reproducing biased language, which can perpetuate stereotypes or prejudices if not properly addressed.

These issues appear even when all other stages are balanced. A perfectly curated dataset still passes through layers, activations, and optimization routines that prefer some patterns over others. This means two models trained on the same dataset can behave differently because their internal assumptions differ.

Addressing Bias

So what can you do about this?

- Use multiple annotators and compare their responses. Metrics like Cohen’s Kappa can help quantify disagreement.

- Develop clear, example-rich labeling guidelines that reduce ambiguity.

- Regularly review samples for consistency and provide feedback.

- Rotate tasks or implement breaks to reduce fatigue-related errors.

- Track patterns across annotators: are certain individuals consistently mislabeling edge cases?

- Addressing bias requires a comprehensive approach, including data pre-processing, fairness-aware algorithms, post-processing, and regular auditing using AI tools designed for bias detection and transparency.

Human input is powerful (it adds nuance and judgment that machines lack), but it needs guardrails. A thoughtful data annotation process can go a long way in reducing bias at this stage.

Conclusion

Bias in AI isn’t caused by a single mistake. It’s the result of a long chain of small, often invisible decisions: from how the data is collected to how it’s labeled and interpreted. The key isn’t to aim for perfection, but to build awareness and processes that help detect and reduce bias where it matters most. AI requires transparency, explainable AI, and ongoing evaluation to ensure ethical outcomes.

By actively questioning your data sources, diversifying your inputs, and supporting your annotators with better tools and guidelines, you don’t just build a better model; you build a fairer one. In real-world applications like credit scoring and student success prediction, unchecked bias can reinforce harmful stereotypes and perpetuate social inequalities.

And in a world where AI is playing a bigger role in everything from hiring to healthcare, that makes all the difference.

Explore More

Explore these resources for more on data annotation:

- Data Annotation Top 11 AI Podcasts in 2026 by Categoryat Scale

- (Processed) Data is the New Oil

- Writing Clear Guidelines for Data Annotation Projects in 2026

References

- IBM (no date). What is AI bias? IBM Think: Source

- Inna Nomerovska (Dec 13, 2022). How A Bias was Discovered and Solved by Data Collection and Annotation. Keymakr Blog: Source

- Mukund Srinath and Sanjana Gautam (Apr 29, 2024).Blind Spots and Biases: Exploring the Role of Annotator Cognitive Biases in NLP. arXiv: Source

![Understanding ML Bias in AI Models [2026]](/content/images/size/w2000/2025/12/bias-1.png)